#9: What Is The Value Of Money In A Sinking City?

Venice is a new kind of paradigm for the value of a fixed structure: most are sinking, valuable (for now) but historically significant and hard to change. What can this teach us?

PRESSED FOR TIME?

Everyone knows Venice floods and in the long run, is sinking. But what does this do to the value of a built structure? Who invests when tomorrow has so much uncertainty? Venice teaches us about the profile and conservatism of capital in certain settings. Every city that follows Venice’s course will have winners and losers, they just might not be the ones you think.

WHO THOUGHT A CITY ON WATER WAS A GOOD IDEA?

It’s a fair question, that doesn’t get asked enough: why does Venice exist?

For much of the Dark Ages, Italy dealt with armies advancing back and forth across the region around Venice, largely because it was the one land route to Rome that didn’t involve crossing the Italian/Swiss Alps. Armies typically come with resources to cover land, not water. The safest place for many locals? The lagoon. Twice every day the water in the lagoon drains away and fills up again with fresh seawater: this created a perfect environment for fishing and salt production. There is evidence for a settlement in 600 C.E., and over the centuries it developed as a trading centre, happy to do business with both the Islamic world as well as the Byzantine Empire, with whom they remained close.

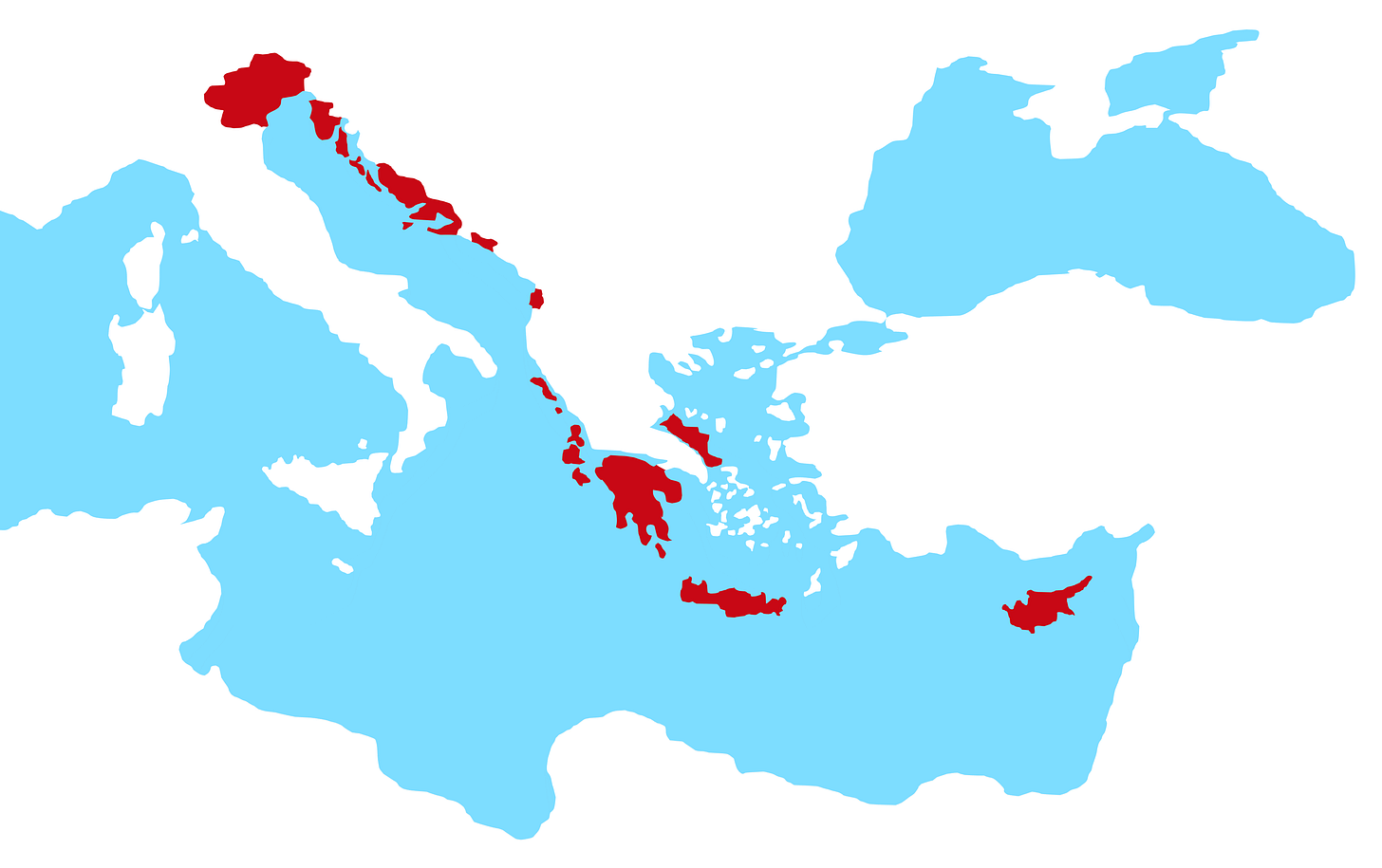

Keeping many friends gave the Venetians many trading partners, and at its peak, the Venetian empire covered the red shaded region below — right across the Mediterranean. Venice’s impact beyond the Renaissance, and to the present day is significant: Venetians gave us sunglasses, modern accounting and the introduction of coffee to Europeans, which the Arabs brought from Egypt. In our language, we also wouldn’t possess ghetto or quarantine without a few chapters from the city’s history.

WAIT, BUT HOW DID THEY BUILD ON THE WATER ITSELF?

Would you believe: all those majestic palazzos are supported by lots of 60 foot wooden piles hammered in close together.

These piles go deep down into the soil, reaching past the weak silt and dirt to a portion of the ground that was hard clay and could hold the weight of the buildings. Normally this would have been a disaster as wood rots, but only when both air and water are present, so in the oxygen starved environment of the water underneath the buildings, the wood was protected (there is a similar foundation effect for places like Boston’s Back Bay and much of historic Amsterdam). The waters of the lagoon then carried an extremely large amount of silt and soil and the wood was blasted by this sediment for years. The wood absorbed the sediment and quickly petrified at an accelerated pace with a resilience akin to stone.

What about the waterways? Periodically, a section of a canal is blocked off and drained so that necessary repairs can take place. If this work is not carried out, the canals will fill with sediment brought in by the tide and materials eroded from the buildings.

The pile system has had drawbacks. Drinking water has always been a problem: during the 1960’s artisan wells were opened across the city which were drilled deep underground for potable water. However, as the water was drained from underneath the hard clay in which the foundations were piled into, the city began to sink at a faster rate. This is compounded by a problem Venice is known for, and many more cities deal with: sea level rise.

In November 2019, a 6-foot-high tide — the second highest ever recorded — pushed by 35 mph winds submerged 80 percent of Venice. The seawater flooded shops, restaurants, residential ground floors and even the Basilica in St. Mark's Square, causing damage in excess of $1 billion.

Venice’s rather celebrated response to this problem of city-wide subsidence and sea level rise was the flagship engineering project known as MOSE.

The project's name is a nod to the prophet who parted the Red Sea. Its construction time frame is also of biblical proportion: the floodgate system has been under construction for the past 17 years and was initially meant to be completed by 2012. But a series of corruption scandals, rising costs and political controversies has delayed the project, which is yet to become fully operational. The project is now estimated to cost €5.5 billion, up €1.3 billion from initial cost projections. And many experts say it might not be enough to protect the city.

Venice is the world’s largest museum, but also our first human settlement on constant life support. It costs money and has unknown timelines for success.

SO HOW DOES VENICE FUNCTION AS A 21ST CENTURY CITY?

Even with the spectre of catastrophe and creeping water levels, the ingenuity is hard not to admire. How does the electrical current pass safely around a city of water? Under the stones of the city’s walkways, cables run from house to house, carefully hidden from view.

In order to criss-cross rivers, the cables run within bridges, passing between islands unnoticed. The same is true of phone lines, as well as water and gas pipelines. How is trashed collected? Garbage men collect waste on foot, with handcarts to wheel the refuse to the edge of larger canals. The trash is then transferred to large boats that ferry it out of the city. Emergency services are also served by boat. Ambulances, police vehicles, and the fire brigade are all stationed strategically around the city’s 124 modern day islands to be of service.

What about mail? Postal services have liveried boats that deliver packages around the city, nipping through the canals like any other postal van on terra firma. A whole host of other goods are also transported by boat. You’ll see small barges stacked high with food, wine, merchandise — any daily necessity that a Venetian might need. If you’ve ever visited Venice for a holiday, your luggage likely travelled this way too.

But all of this has a cost. Venice is the land of the price premium.

IS LIVING IN VENICE EXPENSIVE?

…yes.

Waste collection is three times the same service in the rest of the province of Veneto. On average, food items in Venice cost 18% more than the mainland.

And then there’s housing. Venice is the most expensive city in Italy, with an average house price of €4,467 (US $5,340) per sqm. Renovations are costly, with all materials needing to come in by boat: and all construction schedules are dictated by the weather. Of the entire real estate inventory in Venice, only 61.7% of the houses are occupied by residents. A total of 29.3% of the houses are associated with non-resident use (such as vacationers) and then 9% of the houses are unoccupied (NB: it is possible the non-resident use figure is far higher with 7,000 Airbnbs around the city, many of them undeclared).

So who pays for it all? Venice is not a normal society, with a natural distribution of ages. The birth rate is 1.23, when 2.1 or 2.2 is typical considered the necessary replacement rate. Due to the decreasing number of youth in Venice, many social programs and activities for children have been cut and daycare centers have closed.

With a staggering 20 million tourists visiting Venice in a normal calendar year, the service industry takes up approximately 80% of the job market. Construction, manufacturing and agriculture make up the other 20%. It’s a binary career pathway for a young Venetian, with a small number of options given the economic homogeneity.

By 2030, some demographers predicted there would be no more full-time residents: thankfully the pandemic has halted or reversed many of these trends. It’s predicted that tourism won’t recover to its previous levels until 2023, giving the city time to ban cruise ships and reset.

But the reality is everything in Venice is driven by hierarchy.

Rising waters don’t force Venice to be a different kind of tourism destination. It warps it into a different type of society. Few people are attracted to high premium, high risk locations: they’re usually wealthy, with an ability to write off their Venetian residence in the worst case.

If we need to think in the mental model of hierarchy, then it’s worth asking some questions —

THREE QUESTIONS…

1. Everyone can justify a high price in Venice:

the engineers are designing a flood system that’s never been done

the contractors are lugging in marble tiles for a new palazzo restoration on boats between rain storms

the landlord will make more from renting to a tourist shop than a laundromat or grocery

the restaurant needs to pay its waiters who commute in from the mainland

If everything has an ever-rising price, but only a select few can pay, what’s the end state for those who aren’t wealthy? Are societies with artificial bottlenecks inherently inflationary? And if so, what does that mean if other cities begin to develop a type of climate-proofed preservation district, and are affected by the same forces?

2. Suppose you’re worth €5m: would you buy a palazzo for €3m? Let’s say you would be guaranteed a minimum of ten years of enjoyment before the foundations made it unliveable, and major repairs are needed: would that be a worthwhile tradeoff? To many it would seem reckless to spent close to two-thirds of your net worth on an asset with a looming impairment event, but this is precisely what homeowners in floodplains do around America each and every day.

3. When Venice opens back up after the pandemic, should you visit? Do you contribute to the problems simply by participation? The relationship between city dwellers and tourist flows is not clear, nor their relationship with the resilience of destinations. Venice needs revenue to survive. Which dollar is more valuable to Venice, 10,000 daily visitors paying a €10 access fee, or a millionaire lovingly restoring a structure for ten times this figure, when the investment is emotional and the economic return is minimal? A hard aspect of the flow of capital is it’s very difficult to be morally selective.

Venice’s sea level rise and subsidence challenges will continue, and there will be winners and losers. Money retains its value, but will be pulled in new directions by changing human needs: those needs might seem misaligned to many of us, but they simply reflect supply and demand in a unique environmental setting.

Just because the rest of us don’t live on a lagoon doesn’t mean we might not see similar forces at work when climate pressures bear down on our own towns and cities.

Optimistically,

Owen C. Woolcock

3 Questions I Am Asking Myself This Week

1. An interesting opinion from Noah Smith on Twitter:

“My unified theory of COVID denial is "fear management". People who weren't used to being afraid of things suddenly had something to fear, and didn't know how to deal with it, and felt ashamed, so they denied COVID in order to try to convince themselves they weren't really afraid.”

A corollary for those who feel similar on climate change?

2. Tickets for a nuclear-powered super yacht will cost $3 million for VIPs and be free to scientists and students selected to help study climate change. It launches in 2025. Vanity initiative or a Manhattan Project for the waves? (Article)

3. A sure fire way to feel old? We’re now closer to 2050 than 1990.

If You Read Or Listen To One Thing This Week

MIT Article: What 250 Years of Innovation History Reveals About Our Green Future. An excellent article to make you feel positive about the coming two decades.