#4: How Did A Super Bowl Ad Change The Future Of Electric Vehicles?

Will Ferrell's GM Super Bowl ad, which aired 7th February here in the US, has probably done more to recast electrification than any climate rally or NGO in a generation.

PRESSED FOR TIME?

A Super Bowl ad aired this month and drew new boundaries around the experience of owning a battery-powered vehicle in America. Some day soon renewable energy will power the cars, buses and trains of America’s major cities — but this wasn’t inevitable, and unpicking why helps us to frame the mental models around how other industries will decarbonise.

HI WILL.

For this newsletter, we start with $5.6m of precious Super Bowl airwave time:

If you’ve not seen this ad, a 60 second version of it featured this month in the coveted first quarter of Super Bowl LV.

The facts of the humorous, 90 second grab are fairly simple: Will Ferrell announces that the United States has not adopted electric vehicles (EVs) as quickly as Norway. He punches a globe in disgust, enlists some celebrity friends, shouts ‘Let’s GO America!’ and along the way, shares the key piece of information that General Motors (GM) will have thirty (30) new types of EVs in the market by 2025.

By 2040 or 2050, Americans’ mass adoption of electric vehicles will seem like something that was always going to happen. For that reason, it’s worth stopping to reflect on the enormity of the moment, the company involved, and why this commercial will end up signposting the energy transition more than many activist books or global agreements. So what is really going on in this commercial?

DISSECTING THE COMMERCIAL

ONE: Will Ferrell is post-Trump America. To keep a timelessness to the message, the pandemic appears not to exist, but in every other sense Ferrell represents a weary American masculinity. He is well known, but doesn’t look how people remember him.

With subtle nods to hit shows True Detective and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Ferrell’s a regular American Dad in a typical suburban garage, left to work out why something’s different. America should lead in everything it tries to do, but the ad is trying to shock the viewer into realising how far the U.S. has fallen behind in a race everyone else kept running. Like all great ads, it says something profound without being explicit: there have been costs to America’s internal division, but not all of them obvious.

TWO: The cars don’t look like Teslas. This is a crucial point in the crossover significance of the moment. Many Americans have a friend at the office or golf club in the last five years who took a Tesla test drive and wouldn’t stop talking about it, but as a product Tesla is still associated with the shape of the original Roadster and sporty indulgence.

Ferrell’s car is a Cadillac Lyriq, while Awkwafina and Thompson are driving GM’s new Hummer. The tagline for the Hummer campaign? The Quiet Revolution Starts Now.

This sentiment perfectly encapsulates the hope for the auto industry: that EV adoption will be uncomplicated, apolitical and cost-effective for all parties. Once someone considers a new car for purchase, the brain adjusts, adding the particular model to its list of things to notice. Psychologists call this the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon; more commonly, they refer to it as frequency illusion.

Few things have been studied so meticulously like car sales. People often need to visualise something many times before being comfortable with it themselves. The light truck market that includes SUVs, vans and pickups, is three-quarters of U.S. auto sales. The every-family crossover SUV is one of the most cutthroat markets for any product in the world. Big automakers like GM need to spend to convince, but also not let people know they’ve needed convincing.

Why is EV adoption so pivotal to the decarbonisation story? Because it’s the part of the economy where we spend the most money on things we don’t notice.

THREE: Norway doesn’t matter, American action does. Norway is the MacGuffin, a destination so inconsequential to the commercial’s plot that Ferrell’s final pursuit references three Scandinavian nations (Norway, Finland, Sweden), all of which could easily be each other. None stand a chance if America acts at scale. If America decides it wants to do something, the ad argues there is no competition. Again, the subtle parallel to global coordination on the climate challenge is present.

BUT WAIT, WHY HAS GM ANNOUNCED THIS?

Climate watchers have smiled with some cynicism at GM’s big announcement. Why? There’s a backstory, and it involves a car called the EV1.

In 1990, California enacted a law that forced an auto company to be working towards low emission vehicles if it wanted to sell polluting cars in the state. GM and many automakers fought California for years in the courts, but in the background they worked on the problem, and sure enough, devised a neat little coupe (above) called the EV1 that was all-electric, drove 80mph and had a range of 70 miles on a single charge. They were accessible under a lease-only agreement to thousands of loyal drivers.

But the cars were not especially profitable for GM. The EV1 program was subsequently discontinued in 2002, and all cars on the road were taken back by the owner, under the terms of the lease. Lessees were not given the option to purchase their cars from GM, which cited parts, service, and liability regulations. Incredibly the majority of the EV1s taken back were crushed, with about 40 delivered to museums and educational institutes. Just like that, they vanished and became the pursuit of collectors and enthusiasts. By 2003, lobbyists had successfully chipped away at California’s 1990 EV development mandate and it was taken off the statutes.

As a cautionary tale, GM CEO Rick Wagoner had this answer when asked years after about his biggest regret while leading GM:

‘Axing the EV1 electric-car program and not putting the right resources into hybrids [was clearly my biggest regret]. It didn’t affect profitability, but it did affect image.’

IT GETS EVEN WORSE FOR GM..

When the Trump administration sought to strip California of its power to regulate vehicle pollution, GM joined in the lawsuit when many auto makers including Ford sided with California. In 2017, Mary Barra, GM’s CEO, sat next to Donald Trump when he announced a rollback of climate-pollution rules. GM, in fact, continued to argue that California did not have the power to regulate vehicle pollution until November 23, 2020 — a full three weeks after the election, when the reality of new EV momentum under the Biden Administration should’ve been apparent.

HAS ANYONE SEEN A CHARGER?

On the surface, it would seem like GM hasn’t been punished for waiting two decades to move. EVs are less than 2% of annual auto sales. In one study, 83% of US car owners said they would not consider buying an EV because of battery life and charging anxiety.

A lot of them are right. You have to know how to plug an EV in. You have to count the range and plan driving for that day. You have to not be intimidated by plug shapes or compatibility, or driving up to a charging station running late for a meeting, and seeing all the charging bays occupied. Besides: who should build out the charging stations, the companies or the government? By letting a few companies create the field, do you allow them to seal off a competitive advantage? And how much do power companies need to pull from the grid to service the vehicle fleet?

Range is crucial to confidence. So is the proximity of multiple charging stations. The map below looks like a lot, but not compared to the 156,000 gas stations.

Not all chargers are the same. Tesla outlets only work on Tesla vehicles. Most of the other charging outlets are working towards universal compatibility.

Level 1-2 charging is more typical in the home, while new Level 3 outlets are increasingly common on the open road, though many of the first generations EVs struggle to handle this intensity of recharge.

With even the most basic introductions, it’s easy to see this is not a simple problem.

MAKING A BET, WITHOUT FULL COMMITMENT

Let’s return to GM and where they fit in all of this. The company has been reluctant to use their substantial muscle (and money) to lay out the infrastructure, instead partnering with multiple charging startups and trying to back the winner. In July 2020 GM also announced a partnership with EVgo, to build more than 2700 new fast chargers across the country. Will the strategic locations of these be enough to satisfy the next wave of car buyers?

Finally, let’s consider the small ways a different source of energy generation could lead to habitual shifts. In an interview with CNBC, Alex Keros (Lead EV Infrastructure, GM) said:

In California, the sun burns brightly at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, and there’s an overabundance of electricity. How do we start to match that opportunity and say ‘hey cars, start charging — the sun’s here!’ We need to manage that with utilities in the background so people aren’t even changing their behaviour. If this occurred, we’d be getting cheaper energy, that’s better for the grid, and well as cleaner energy overall.’

This is why it’s so important for a big gorilla like GM to move now. People need to buy EVs and not stress about their performance. Cars need to charge easily and with as minimal a behavioural change as possible.

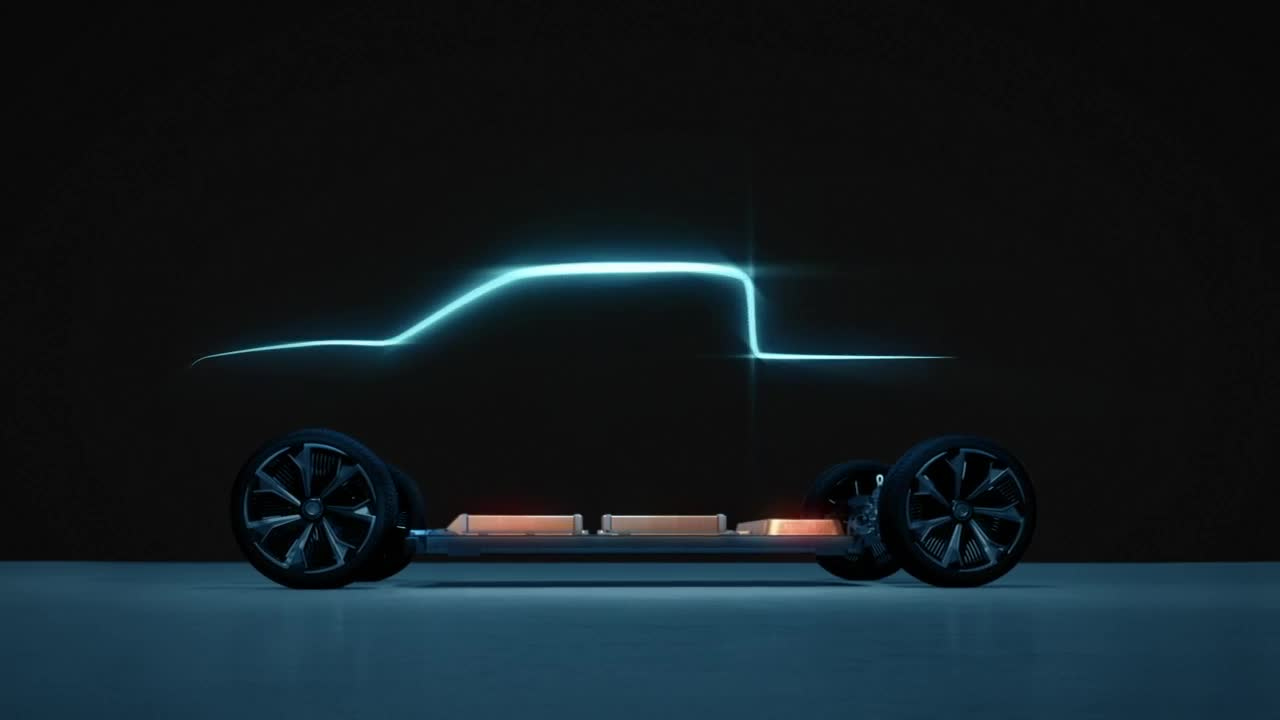

If we consider the imagery of how GM’s new Ultium Battery sits in their new vehicle range, it’s almost like it’s not a piece of the internals. And that’s what the auto industry wants: progress without complication.

SO WHY DOES THE GM COMMERCIAL MATTER SO MUCH?

Iconic ad campaigns have the power to reshape consumption and association with even a sentence or image: just ask Apple, Coca-Cola, Nike or Tiffany’s. This GM ad matters because it’s the closest a $57b market cap company will go to admitting they got it wrong. The remarkable part of the commercial is its ability to slot into the haze of car commercials each and every year, with a marketing message that normalises EV ownership and wipes clean twenty years of missteps and intransigence. When the EV design, performance and charging puzzle is solved, our world will be decarbonised in many ancillary ways that our own eyes won’t even notice.

The implications of that are far-reaching indeed.

Optimistically,

Owen C. Woolcock

3 Questions I Am Asking Myself This Week

1. My wife and I purchased a secondhand Audi Q5 (2010) last October to navigate the Massachusetts winter, but what about our next car? Would I buy or lease an EV? And what conditions would need to be satisfied in my own mind to take the plunge?

2. While Bill Gates was promoting his new book this week, he was asked “What is the one thing you want everyone to know about climate change?” His answer? 'Well, anyone who thinks [the response] is easy should know that it’s hard. And anyone who thinks that it’s impossible should know that it’s possible, but hard.’ Well said.

3. In late January, GM announced that it wouldn’t have any gas-powered cars to sell by 2035—because that was its deadline for going all electric. This is the surest sense yet that my son born in 2020, who will be 15 in 2035, is quite likely to never drive a gasoline powered vehicle.

If You Read Or Listen To One Thing This Week

The Dave Letterman Show: Tom Hanks espousing his love for electric vehicles on Letterman in the late 1990s. Yep, the technology existed and was being sold at scale nearly a quarter of a century ago.

References:

Auto sales data: Edison Institute, 2019 Auto Sale Figures

CNBC, How Tesla, GM And Others Will Fix Electric Vehicle Range Anxiety (Youtube):