#25: What Does Italy's Drought Tell Us About The Future Of Southern Europe?

A severe drought in northern Italy is a portend for the future; not only the weather, but also the supply shortages, debt and inflation implications. All of the Mediterranean should take note.

PRESSED FOR TIME?

In a world with plenty other news stories, it might’ve been missed that Italy’s northern agricultural bedrock is experiencing its worst drought conditions in two decades, and the lowest river flows in 70 years. If you like prosciutto, it’s an important story. If the connection between weather, debt, inflation and creditworthiness interests you, it’s an important story.

IT ALL STARTS (AND ENDS) WITH WATER

It’s no surprise that water is pivotal to just about everything we do. If you live in the Western United States, you are likely showering in and drinking water that originated from snow, as snowmelt makes up around 75% of the region’s water supply. In many parts of Europe, the story is no different.

What we’ve known for some time is this: as rainfall patterns, evaporation, snowmelt timing, and other factors change, renewable freshwater supply is affected. Some parts of the world like South Africa and Australia are expected to see a decrease in water supply, while other areas, including Ethiopia and parts of South America, are projected to experience an increase. Certain regions, for example, parts of the Mediterranean and parts of the United States and Mexico, are projected to see a decrease in mean annual surface water supply of more than 70% by 2050. Such a large decline in water supply does two things: (i) it exacerbates chronic water stress; and (ii) it increases competition for resources across sectors.

A Plain English way of saying the above is every person, company and industry thinks their case for water use in a time of shortage is greater than many others.

An illustration of this competition is the grim season facing northern Italy — one of the most concentrated regions of culinary wonder in the world, and home to the origins of pesto, risotto, focaccia, parmesan cheese, prosciutto, bologna (known as mortadella in Italy), Lambrusco and balsamic vinegar, to name just a few. Meagre winter snowfall in the Alps, which has affected the flow of water from the mountains into northern Italy, and more than six months with almost no rain since, has left many producers on the brink of failure.

The crisis is the latest setback for Italy’s struggling economy and exacerbates already mounting inflationary pressure as the country deals with the impact of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Italy is Europe’s largest rice producer, growing specialised varieties, mainly in Piedmont and Lombardy at the foot of the Alps using a system of irrigation channels that funnel water down from the mountains. Northern Italy’s Po river valley generates about 14% of Italy’s agricultural output, much of it from the livestock that produces the country’s famed hams and cheeses. Yet the shortage of rain means parts of the river have dried up completely.

According to a warning issued in March by the EU Global Drought Observatory, Italy’s reservoir levels were the lowest since 1970. Water in the picturesque northern lakes Como and Maggiore, which are typically fed by Alpine snowmelt, is also a fraction of normal levels, at 26% and 12.4% respectively. The level in Maggiore is the lowest since the 1940s.

Italian farmers are counting the costs. Coldiretti, Italy’s national farmers’ confederation, estimates that the shortage of water has already caused €3 billion worth of damage, with cereals such as rice, maize and durum wheat, used in pasta, particularly hard hit (NB: don’t be shocked if the nice pasta in your local shop sees a price hike). Animals are suffering from heat stress, with dairy cattle in areas experiencing unusual high temperatures producing significantly less milk. The growers’ association estimated that a third of the country’s agriculture output is at risk.

“We have about 30% less production of milk and about 30-40% per cent less of cereals and maize,” said Fabio Bonaccorso, a Coldiretti spokesman. He warned that Italian farmers would be forced to import the maize to feed livestock, adding to pressure on an already tight global market that is struggling to cope with the disruption to Ukraine’s grain and cereal exports caused by the war. “If you haven’t got enough maize, you have to pay to buy crops from abroad, because you have to feed the livestock,” he said. “Without feed, you cannot produce milk. It’s a chain.”

In the farmer’s own words, the supply chains from water disruption tally up fast.

Why does this matter for us? Because we as the consumer wear it. Inflation in the retail price of the goods that do reach our shelves is the natural result of fewer quality Italian goods reaching the market.

THEN THERE’S THE HYDRO…

The drought also threatens the country’s hydropower generating capacity as well as its agricultural output. Hydropower facilities, mostly located in the mountains in the country's north, provide almost one fifth of Italy's energy demands. An industry source told the AFP that while the situation was constantly changing, estimates for the first six months of 2022 suggest nationwide hydroelectric generation will be almost half the equivalent period of 2021. When each European nation is trying to wean itself off Russian gas reliance, this drought couldn’t be less timely.

WHAT IS IT LIKE TO LIVE WITH LESS WATER?

The funny thing about a generation exposed to water restrictions in childhood is you come to know no different. In Western Australia and my home town of Perth, water restrictions were as common as sunrise and sunset. Dwindling rains have decreased runoff into Perth’s reservoirs by 91% since the 1970s, forcing an increased reliance on groundwater. Australia’s aquifers have been drained at unsustainable rates for decades, but Perth is now actively replenishing them by pumping a portion of its treated wastewater into shallow aquifers that naturally filter and store the water until it is needed again. This process of augmenting freshwater supplies with treated wastewater, called Indirect Potable Reuse, is about the only chance urban water supplies have to manage ongoing needs in fickle rainfall years.

For all our wastefulness in many parts of the environment, Australia is pretty good by global standards at using less water. Many products are rated and labelled for water efficiency, with homes increasingly adopting water-saving features from shower heads that regulate flow to dishwashers that use just 12 litres of water per load, a mere 10% of traditional rinsing and washing. The power of water-conscious regulators shows that if a product isn’t conservative enough, it doesn’t get into the country to be sold. More than a quarter of Australian homes collect and store rainwater for domestic use, contributing around 177 billion litres to residential water supplies.

Why did all this happen? Because the problem became real. Adaptation was necessary.

In Italy, it’s a different story — with an abundant snowmelt system from the Alps that farmers and politicians never thought would run dry. Last Friday, the northern region of Lombardy called a state of emergency due to the drought, and recommended, among other measures, a halt to non-essential water use, such as street washing, watering parks, playing fields and playgrounds. Barbers have even been prevented from washing a client’s hair twice in parts of Bologna.

Prime minister Mario Draghi’s government has declared a state of emergency across five regions including Lombardy, with an initial allocation of a total of €36.5m in aid for the most affected areas.

What does every drought or climate change aid package do to a national balance deficit? It adds to the amount needed to borrow, and that affects the cost of debt in the long run. €36.5m is a small number for now but this is probably something we don’t discuss enough.

Sadly this isn’t a story unique to Italy. Climate modelling shows the share of irrigation water supply from snowmelt decreases in almost all snowmelt-dependent areas:

33% down to 18% in the San Joaquin Basin in California, USA;

29% down to 9% in the Po Basin in northern Italy.

Other areas strongly affected by such changes are the Rhône Valley basin in Switzerland and France, and the Ebro basin in Spain. In other words, each of Europe’s traditional food basins will be adjusting to a new reality. If water systems that cross regional and national borders feels too esoteric, consider this:

By 2050, the climate in the French port city of Marseille could more closely resemble that of Algiers today.

In other words, much of the southern Mediterranean will soon feel like North Africa. It is hard to imagine the food produced in these areas continuing to be so abundant without serious agricultural innovation.

WHAT ARE THE LESSONS FROM ITALY?

If the news of Italy’s drought has made you feel a little despondent, and the thought of even more expensive prosciutto and parmesan cheese doesn’t fill you with joy, let’s take the opportunity of Italy’s woes to practice a different type of mental modelling. What do I mean by this? It’s worth investors and consumers reflecting on the following:

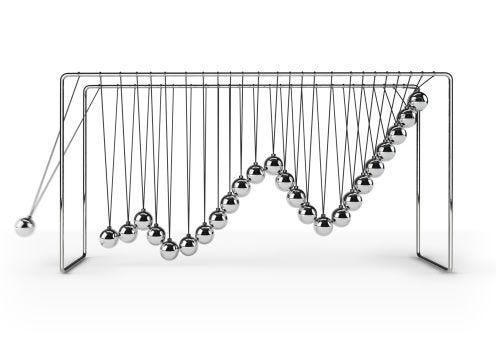

The mind wants to hear disruptive news on something like a drought and place it in a sequence of events, almost like a Newton’s Cradle.

We desperately want to link action and response sequentially because it’s the simplest way for our brain to absorb detail and think analytically.

Climate change doesn’t really allow for this.

We’ve seen from this example alone that reduced snowmelt and drought conditions are almost symbiotic, and affect irrigation infrastructure, and hydroelectric power, and livestock milk production, and produce ingredients, and water consumption allowances in non-correlated industries, and inflation in the broader economy — both inside Italy and overseas in the markets where Italian made food carries such a premium (and is difficult to substitute).

What’s a better visual analogy?

Even this doesn’t encompass the circuitous, multi-time scale nature of the challenge.

In other words, thinking about climate disruption asks us to think differently, almost like a game of chess with implications in every direction.

ONE LAST THOUGHT EXPERIMENT…

Suppose you are the owner of a rare bottle of Piedmont or Lombardy wine.

Then consider that areas known for the quality of their wine grapes risk losing their prominence on the viticulture map, while nontraditional growing regions may gain advantage.

What happens to the value of a famous wine from a changing region? Does it develop greater scarcity, or does it come to be seen as part of a dying history? How would you frame the investment if you owned one bottle? How would you frame it if you owned a hundred bottles?

It’s these types of questions that we benefit from asking earlier, and often. We should have some faith in the capacity of historic food regions of the world to get creative when faced with an existential crisis; but we also can’t be naive to the scale of disruption coming. One drought is difficult enough for northern Italy’s farmers, but by 2050, drought conditions are expected to prevail for at least six months of every year in many parts of the Mediterranean. Asking how that transition unfolds, for whom and on what timescale, is just as important as the adapting.

Optimistically,

Owen C. Woolcock

3 Questions I Am Asking Myself This Week

1. How do European cities find a way to stay cool when heat waves will be increasingly normal?

2. No sooner had I finished this draft, did the New York Times publish a digital story on the very same topic:

3. Did you suffer damage from a hurricane or flood in the past few years? The NYT is trying to tally up the real experience of repairs and costs. Take the chance to participate if you’re eligible:

If You Read Or Listen To One Thing This Week

Shamelessly, a webinar involving yours truly! And a deep dive on the mental model employed in our day job at Climate Core Capital.