#22: What Did The Latest McKinsey Report Tell Us About The Cost Of A More Stable Climate?

A McKinsey paper released last week is clear-minded, helpful and thought-provoking on an important topic for all of us: what's decarbonisation going to cost us, and what are the options?

PRESSED FOR TIME?

A new, shiny 224-page McKinsey report (summarised for readers this week) shows there is potentially a $3.5tr annual shortfall in the commitments made worldwide already to get to net-zero by 2050 (and a 1.5C world), and what is actually needed. The economic exposure to the transition will not be uniform across sectors, geographies, communities and individuals. This matters for investors because the roadmap of where economic pain and opportunity might occur can be found in the findings.

WHY IS MCKINSEY WORTH LISTENING TO?

It won’t shock anyone reading this that the management consulting firm McKinsey & Company hires smart people. Their near-century of success comes from breaking down big problems into manageable initiatives and outcomes. We can tend to read big white papers or research, and glaze over: but the firm has made two of the most important contributions to climate change in my working life:

The Cost Abatement Curve (2007)

In 2007, environmentalists, corporate executives, academics, campaigners, and policy makers were often talking at cross-purposes and needed a shared vocabulary—the McKinsey Stockholm office took a small project for a Swedish utility company, and produced a globally crucial tool, all on a single page.

The abatement curve presented the relative cost-benefit of each option, and opened the way to a more dispassionate, fact-based conversation about what to do. Truly, it has changed the world. In the bottom-left corner were the simplest, cheapest actions, and in the top right were the hardest and most expensive, but also the most impactful based on gigatons of CO2 abated per year. It has been recreated for countries and industries, and remains a guiding roadmap for the world’s efforts as it is revised and updated over time.

Climate Risk and Response (2020)

In one of the last in-person events I attended before the pandemic (Jan ‘20), McKinsey and the globally influential Woods Hole Research Center hosted a launch in New York of their joint paper examining the economic costs of physical climate risk. It remains the document I send every interested party and potential investor who’s interested in understanding the scale of the challenge.

It is impossible to finish reading this paper and not come to realisation that climate change is about wealth disruption, and wealth destruction. It has many profound conclusions, but one of the most unforgettable and disturbing is their forecasts for lethal heat stress. Lethal heat waves are defined as three-day events during which average daily maximum wet-bulb temperature could exceed the survivability threshold for a healthy human being resting in the shade (in short, without very generous air conditioning assistance, there’s no escape).

Under an RCP 8.5 scenario (i.e. business as usual), urban areas in parts of India and Pakistan could be the first places in the world to experience heat waves that exceed the survivability threshold for a healthy human being, with small regions projected to experience a more than 60 percent annual chance of such a heat wave by 2050.

The regions of the subcontinent examined are populated by 160-200 million people. There is no pleasure in typing this, but McKinsey’s findings effectively amount to a better than even chance people will turn on the news in the middle of this century to watch leading news stories of low single digit millions (yes, millions) of people dying in single heat wave events. Truly, Kim Stanley Robinson’s terrifying opening chapter of Ministry of the Future, coming to fruition.

WHAT DOES THIS NEW MCKINSEY REPORT SEEK TO UNDERSTAND?

If anyone needed reminding, the mission of getting to net-zero by 2050 is not a passing political vanity project, but a collective effort to avoid things we all struggle to imagine — a different and more unstable world, with irreversible consequences.

McKinsey knows significant challenges stand in the way, not least the scale of economic transformation that a net-zero transition would entail and the difficulty of balancing the substantial short-term risks of poorly prepared or uncoordinated action with the longer-term risks of insufficient or delayed action.

The work for this paper started with two big questions:

What will it cost the global economy to reach net-zero emissions by 2050?

When does the money need to be spent? Earlier, smoothly, or toward the end?

The project looked at the economic shifts needed to reach net-zero by 2050

Demand

Capital allocation

Costs

Jobs

…in sectors that produce 85% of overall emissions.

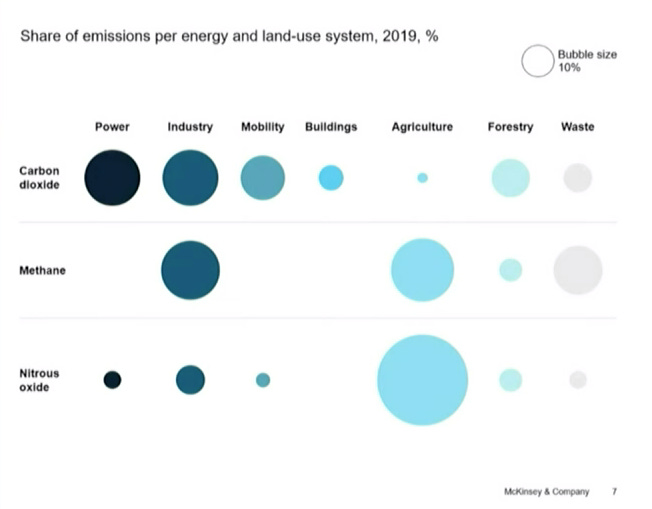

Each of the seven major energy and land-use systems contributes substantially to emissions, and every one of these systems will thus need to undergo transformation if the net-zero goal is to be achieved. Transformation is a euphemism in this setting for political pushback, protests and asset write-off pain—all of which can’t be orderly.

They also looked in-depth at 69 countries. What did they find?

The key goal from this graphic is to understand how great each country’s exposure to the transition will be, through a transition exposure score. Intuitively the countries who will find net-zero the most painful for their economy are those who produce a lot of fossil fuels, or those who are still developing and can’t create a renewable energy infrastructure overnight.

Another important point? No country has a transition exposure score of zero. But some will feel more pain than others.

WHAT’S THE BIG HEADLINE?

What garnered a lot of news when this report was released? There’s a $3.5tr shortfall.

About a third of that number is needed for developing countries, whose wafer-thin budgets and policies are focused on bringing their populations out of poverty—and typically with the assistance of cheap (dirty) energy.

Another key point is the money needs to be spent sooner, and then taper.

Energy costs are crucial in this. McKinsey found that in the long run, it is conceivable that the delivered cost of electricity could be on par or potentially less than 2020 levels, because renewables have a lower operating cost—provided that the power system can find ways to overcome the intermittency of renewable power and build flexible, reliable, low-cost grids. The key message there? Delivered cost of electricity could increase in the near term.

WHY IS THE MCKINSEY REPORT IMPORTANT?

These numbers are larger than some past estimates have assumed, which points to the scope of the challenge. McKinsey is not a climate skeptic think tank chirping negativity from the sidelines; they are one of the most proactive entities in the world on sustainability, so their dispassionate announcement of the price tag is a reality check for everyone. Relative to the size of the global economy, the numbers might look larger still—equaling between 6% and almost 9% of global economic output.

THESE ARE ALL BIG NUMBERS, WHAT DOES IT ALL REALLY MEAN?

If you add up all the commitments, we don’t get to 1.5C.

Also commitments on paper have complexity and challenge. We shouldn’t be surprised by this complexity, energy and land use patterns that took two centuries to develop are being reordered in a generation. At least that’s what we’re attempting.

Is it worth trying to find the extra commitments? Absolutely.

Another just-published report, by Aon Plc, found around $330 billion in weather and climate-related economic losses in 2021 alone, the third-costliest year on record after adjusting for inflation. The European Central Bank is looking to a climate stress test that factors in single-year losses of up to 45% in homes exposed to flooding, wildfires and other climate risks. Overall global climate damages easily exceed the cost of action, justifying limiting temperatures to 1.5°C through pure economic reasoning.

Comparing costs now with benefits later is precisely the virtue and the political stumbling block of the low-carbon, high-efficiency transition. As NYU economist Gernot Wagner put it in a Bloomberg column:

Someone does indeed need to spend the money now.

It’s important to mention the McKinsey analysis is not a projection or a prediction and does not claim to be exhaustive; it is the simulation of one hypothetical, orderly path toward 1.5°C using the Net Zero 2050 scenario from the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), to provide an order-of-magnitude estimate of the economic costs and societal adjustments associated with net-zero transition. It’s one road the world could take—probably close to the ideal road.

The findings are a call to greater action, and greater urgency. The McKinsey report makes it clear that the political headaches are well worth the fight. After all, on net, the transition implies more investment, more economic growth, and also more jobs—to say nothing about a more liveable planet and newer, better technologies, from well-insulated homes to better and more efficient modes of transport.

HOW SHOULD INVESTORS THINK ABOUT THESE FINDINGS?

If you invest in the world around you (and let’s face it, we all do even indirectly), it’s worth asking the following, based on what we’ve just learned:

For each company I invest in, what will be the asset base left when this transformation has taken place?

If oil, coal and natural gas needed to be phased down, and it’s plausible internal combustion engines aren’t made for private vehicles anywhere in the world by 2040, what would this mean for in the country I live in?

What are the places in the world that will be the most liveable, the best adjusted, the most flexible as this transformation unfolds?

Where might extreme strips of transition risk develop? That is to say, where are places and geographies likely to experience physical extremes, stranded assets, economic dislocation and a weak case for further investment?

Net zero transition is just that, a transition. It’s not a switch. It’ll be easy to play a cynical route, divest fast and wait for trend movements to invest again. Unfortunately what’s required is a systems lift, with public and private finance acting in constant coordination. Another question to ask is: what will this mean for competition as we understand it?

As a final thought, it’s worth returning to a statement made earlier: energy and land use patterns that took two centuries to develop will need to be reordered in just three decades. It’s impossible to imagine this being orderly.

But what is the counterfactual of a disorderly transition? What is the counterfactual of doing nothing?

McKinsey has made another valuable contribution — our collective effort to parse out what it all means continues.

Optimistically,

Owen C. Woolcock

3 Questions I Am Asking Myself This Week

1. What does this Bloomberg graphic say about the politics of buying an electric vehicle?

2. As many electric cars are now sold in the space of a week as in the whole year of 2012. To put it another way: the passenger electric vehicle market grew 50x in a decade.

3. A great initiative that begs the question: why doesn’t the city I live in do this?

If You Read Or Listen To One Thing This Week

A great podcast from Harvard Business School with a public actor thinking about the implications of climate change more than most — the U.S. Navy.