#21: What Did 2021 Teach Us About Climate Investing?

2021 taught us a few key lessons, and offers big hints on the extent to which capital will follow a theory of change — but only to a point.

PRESSED FOR TIME?

2021 has been a big year in climate investing: initiatives (and disappointments) connected to Glasgow and COP26, Tesla and Rivian’s continued meteoric rises, and activism on the part of central banks to improve corporate disclosure and reporting. But the year also proves a few deeper lessons for the coming decade — money will move in ways we won’t anticipate, ideas will take time to prove, and leadership will undergo a major renewal.

WHAT HAS HAPPENED THIS YEAR?

If you follow the financial markets, it’s been hard to miss the movement of money into anything ‘green’. Issuance of sustainable loans and bonds, where proceeds are supposedly earmarked for environmental projects or to further a company’s social goals, exceeded $1.5 trillion, including about $505 billion of green bond sales; ESG-focused exchange-traded funds attracted almost $130 billion in 2021, up from $75 billion a year ago; and investment in early-stage climate tech companies approached $50 billion.

These are big numbers. On the $50 billion climate tech investment number, it’s worth remembering the average VC investment in America is around $2.4 million, which goes into a number like $50 billion over 20,000 times. That’s not especially scientific math (hardware-heavy startups often seen in the climate space usually require higher initial investment levels), but the point still stands that a lot of new firms and ideas are getting their chance. If just one of them finds an industrial scale way for algae to absorb carbon dioxide into the ocean (which it does naturally, and more efficiently than trees), or green steel, or a safe next-generation nuclear deployable through the suburbs by 2040, then the return on investment is huge. The attitude of Climate and Money has always been there’s always room for optimism if one is so disposed.

But the numbers are the numbers, and not everything went one way in 2021. The S&P Global Clean Energy Index, which includes companies like wind-energy giant Orsted AS, Spanish utility Iberdrola SA and Sunrun Inc., the largest U.S. residential-solar company, has declined 27% so far in 2021, after more than doubling in value last year.

Adeline Diab, head of ESG research for EMEA and the Asia-Pacific region at Bloomberg Intelligence, put the outlook well in a letter on 21st Dec: “Despite mounting catalysts with the U.S. infrastructure plan and EU taxonomy requirements, the clean-energy sector may remain exposed to uncertainty linked to government support such as stimulus delays or incentives-cuts announcements, the most recent being in California [where subsidies have been rolled back for solar].”

Shares of renewable energy stocks hit another speed bump in December when U.S. Senator Joe Manchin, a conservative Democrat from coal state West Virginia, shocked his own party by announcing his opposition to President Joe Biden’s economic plan, which includes a landmark investment in the climate fight. Manchin, whose vote in an evenly-split Senate was needed in the face of universal Republican opposition to significant efforts to fight global warming, has undermined Biden’s bid to address the climate crisis. Biden’s approval rating is low (-5 on current ratings), and with the GOP likely to take the House and Senate in 2022, this legislative window might be the best hope for much of the decade if government stimulus is to play a large role in decarbonisation.

WHAT ARE THE HORSES TO BACK?

Let’s assume Manchin holds his ground and major climate investment doesn’t come from the U.S. government. What or who are the most likely actors in the private sector, and where is alpha likely?

The place the market usually starts is the electric car (or EV). It’s with good reason: EVs have far fewer moving parts than their internal combustion engine counterparts, and require less servicing over their lifetime — the sort of servicing on which dealers and parts suppliers make a good deal of their revenue. How cars are built, used and refueled become completely different in a majority-electric fleet.

The simple truth is for all the hype, a lot does change when many more of us are driving electric.

The market capitalisation of Tesla, Rivian and Lucid Motors now make them worth a number almost equivalent to the entire automobile market. Each of them is worth more at the time of writing than Ford or GM. An astute stock analyst will ask: ‘this assumes these three new entrant auto companies will sell close to every car produced on the planet. That can’t be possible.’ And they’re right. These new entrants have overcome this valid criticism of their valuation by saying their total addressable market is climate change itself.

Tesla wants to eventually sell you a slick touchscreen switchboard in your garage where they manage household energy and sell unused power back to the grid for you. Each of them wants to help power your needs off-grid. So far the market likes the story. Since going public in July through a SPAC deal, Lucid has watched stock prices almost double. Its market cap still pales compared to Tesla’s, which has shot into the stratosphere over the past year to beyond $1 trillion. But the implication is that electrical vehicle fever is only just beginning. Fellow electric carmaker Rivian went public in November, and one week into its life on NASDAQ, it had a $140 billion market cap, making it more valuable than General Motors. Rivian’s IPO actually ranked as the world’s biggest of 2021, helping to catapult it into the largest U.S. company with no sales.

Did anyone believe in 2003 that Apple would move from computers into phones, an app store, watches and a subscription TV channel with native content? An investor’s bullishness in electric automakers is entirely dependent on one’s confidence in their ability to ‘ring-fence’ advantage, and then expand heavily into areas we can’t imagine.

Other climate startups with high velocity, but not yet at the public IPO stage include:

AMP Robotics, a Louisville, CO startup that’s taken $74.5 million of investment and created an AI-powered robotic system that can recycle waste. The technology they’re using can reportedly identify recyclable materials with an accuracy rate of 99%. If correct, this technology has a chance to completely reorder and optimise the 2.01 billion metric tons of municipal solid waste (MSW) produced annually worldwide.

Redwood Materials is another ‘unsexy’ service provider (but with $795 million in corporate and other investments), helping recycle batteries, electronics, and end-of-life products with processing and refining technologies that produce key elements for circular supply chains. A simpler way to say that is they make hard, chemically impacted items useable again. The genius of the business lies in getting into upfront contracts for Amazon, Panasonic and others, determining end-of-life recycling needs, and planning for them at the outset.

Form Energy, based in Somerville MA, have received over $368m in investment and generate $25m annually already from a challenge that can and must be solved: making batteries specific to solar and wind energy, so they can store their energy for extended periods of time. The wind doesn’t always blow and the sun doesn’t always shine, providing the major drawback of renewable energy. Form has developed a battery it says can discharge electricity for 150 hours straight.

Deep-pocketed investment firms such as TPG, Apollo Global Management and Paulson & Co. in recent months have plowed hundreds of millions of dollars into companies like Form, which make what are called long-duration batteries. Unlike mobile-phone or electric-car batteries that can deliver electricity for about four hours straight, long-duration batteries can discharge for longer periods, ranging from six hours to several days, and store far more power.

The workhorse of Form Energy’s battery is a cheap, abundant element: iron. A collection of the batteries can fill entire warehouses and discharge electricity for nearly a week.

A question ordinary retail investors would be fair to ask is: when these companies eventually IPO, do I still get to access a meaningful part of the growth story?

In some ways, no. But the large investors mentioned above have bet on many horses who didn’t make it by the time AMP, Redwood or Form prove to be viable, and so investors like you and I don’t take on those losses either.

COMMON CHARACTERISTICS OF THE WINNERS

Some commonalities stand out from the list of companies above, all who’ve been big parts of the climate investment story in 2021, in either public or private equities:

The winners often start with a major technological breakthrough, and use it to land and expand into a larger product suite. Was home energy use an intuitive connector from car batteries like Tesla saw? Was it readily obvious that an end-of-life recycler could work with solar farms at installation on their long-term panel recycling timelines as Redwood is doing? It looks clear in hindsight, but takes imagination in the moment.

The winners built something America needs first, and the rest of the world will need thereafter. The United States needs electric vehicles and charging station infrastructure to be expanded. It needs to extract the valuable parts of phones, computers and power tools. It needs to identify waste without hands sorting through sharp and decaying objects. It needs to store solar and wind energy. It makes sense to solve these problems first in one of the richest countries in the world with a well developed investment ecosystem.

The winners start as (relatively) small teams, offering options to college-educated talent (science materials, engineering, sales and IT grads mostly), and a mission-driven career with a potentially lucrative pathway. For many the idea that some will profit handsomely from the climate crisis is jarring. The reality is hard problems need many great minds, and many people are motivated by different things.

With the rare exception of the EV makers, the winners are unsexy. Energy grid compatibility, temperature intensity in manufacturing, or the chemistry of plastics composition is pretty detailed stuff — and hard to make exciting in a pitch deck for those without engineering backgrounds. It’s crucially in these domains where so many of the gains need to be made.

EXCITING IDEAS, BUT WHO WILL LEAD?

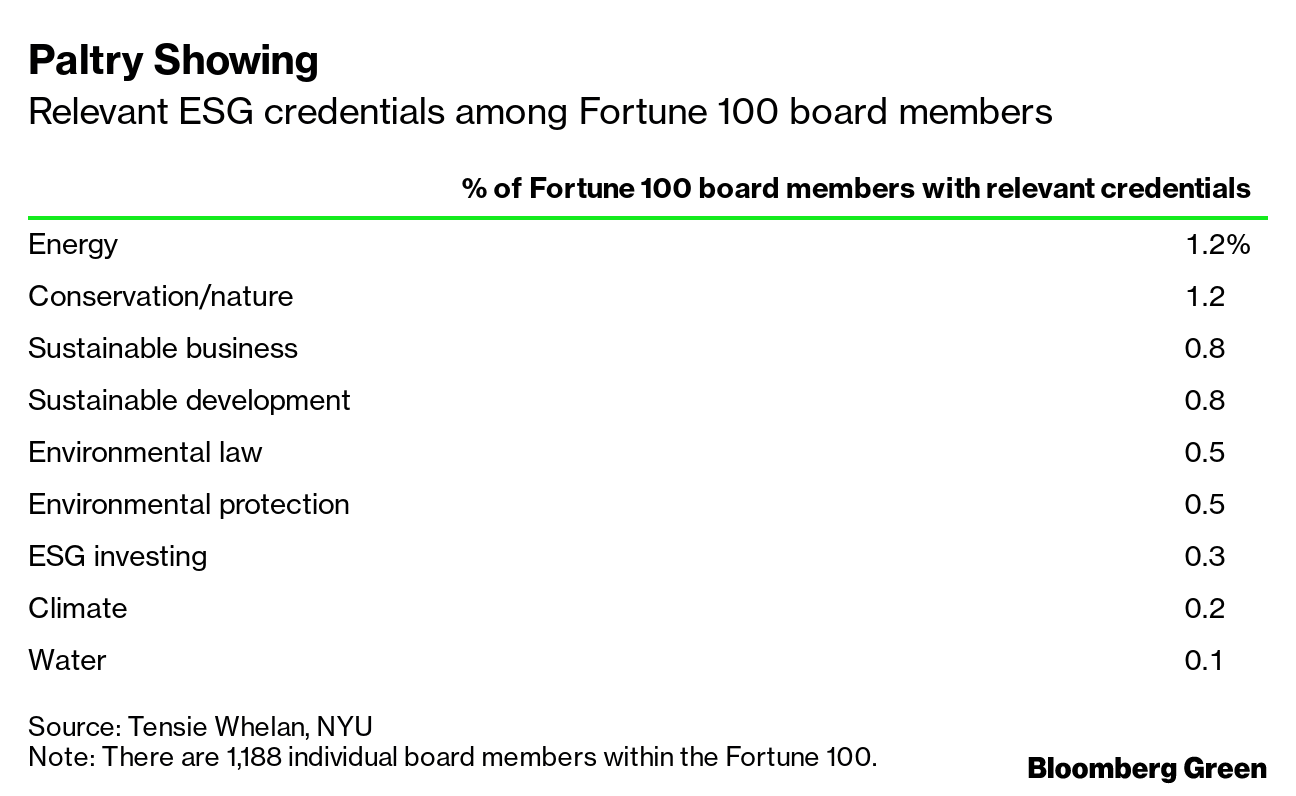

Another important part of the 2021 story is in leadership. A culture shift for the world’s corporate giants is underway, and one best illustrated in a study done by NYU’s Tensie Whelan. As of April 2018, 5% of the nearly 1,200 board members of Fortune 100 companies had experience with workplace diversity, and 2.6% had experience with accounting oversight. Barely 1% had any experience with energy or conservation, the two highest-ranked categories in Whelan’s study. Three-tenths of a percent of the Fortune 100’s board members had experience with ESG investing; 0.2% had experience with climate.

The data is three years old and there will have been marginal improvement. But this is symptomatic of the broader societal story around Boomers transitioning out of power roles, and younger generations (with far longer timescales of exposure to the risks) having a larger say.

Boards who don’t regenerate will see their credibility in the market suffer.

When people ask who is decarbonising with purpose, the best hint of commitment to action lies in the profiles of the board and management team.

2021 IN SUMMARY

If you’re a skim to the bottom kind of person (and that’s OK, it’s New Year’s Eve!), the above could be summarised in the following way:

The money is moving, but that movement of capital will still be volatile

The winners will be underpinned by engineering fundamentals, and an ability to expand beyond their original breakthrough

The big gains from climate breakthroughs will be largely made before retail investors access the security, but that’s OK because the companies that do reach the public markets will have opportunities for multi-decade dominance

The corporate boards of America probably don’t appreciate how underqualified they are for the issues that really matter to the next investment demography

If asked to summarise the last year of Climate and Money newsletters, it would be with the following: the problem of decarbonisation is never fully solved, nor a cause worth giving up on. In any given hour of the day, these could both be understandable conclusions. But it’s a story of fragments and increments. There will be pain and suffering and unequal resources to adapt. There will also be magic and ingenuity and profit and many ways to be part of big mission-driven outcomes.

I wish everyone who’s been part of this journey over 2021 the very best for the coming year, and look forward to seeing what 2022 brings for Climate and Money.

Optimistically,

Owen C. Woolcock

3 Questions I Am Asking Myself This Week

1. Here’s the breakdown of that $50b climate investment number by industry category. What do you see, and what makes you excited?

2. Big news came out for the mortgage markets. What characteristics of the ‘Big Short’ might we see in localised ‘Big Climate Short’ events?

3. Harrowing footage taken from a passenger aircraft of the Colorado fires in the last 48 hours; so rare because we seldom fire from the sky:

If You Read Or Listen To One Thing This Week

A great article from earlier this year on the ways those of us who own a home and want to make a difference can do so: