#20: What Is Ecological Leninism, And Why Is It An Idea We Should All Understand?

A provocative thinker named Andreas Malm has detailed a far-left response to the climate crisis, that financial markets and investors would be foolish to ignore.

PRESSED FOR TIME?

Ecological Leninism is the idea that we’re beginning an age of crisis, and that era of crisis will prompt some new confronting ideas like the destruction of fossil fuel property. Much of this stems from Lenin’s approach and thinking during the Russian Civil War (1917-1922), where he proved himself quite adept at fighting fossil fuel interests. Even if one doesn’t agree with these ideas, is likely to be copied by some on the Left in the coming decades. Financial markets and investors would do well to think outside the box and understand this movement’s logic.

IMPORTANT: This issue contains the evaluation of a new political idea that the Climate and Money audience might find inconsistent with their own politics and worldview. As our parents taught us, we learn by delving deep into new perspectives, and in this spirit, I recommend taking Andreas Malm’s arguments seriously for the length of this newsletter, even if you don’t consider yourself a Marxist or come away in agreement with any of it.

WHAT IS TOO MUCH ESCALATION?

In the summer of 2013, while on assignment for The Nation, journalist Wen Stephenson stood interviewing the young organisers of Tar Sands Blockade, the radical climate justice group that had been engaged for more than a year in a nonviolent grassroots direct-action campaign against the Keystone XL pipeline. At one point in the interview, an organiser said to Stephenson:

“The industry has shown every intention of escalating the climate crisis beyond certain tipping points… We need to ask ourselves, what does escalation look like? What could possibly be too escalated?”

WHO IS ANDREAS MALM?

This question on escalation has been on the mind of a Swedish Marxist thinker the last eighteen months, and arguably much of his adult life. Andreas Malm, an economic historian at Lund University in Sweden, has written a compact new book, a manifesto of sorts, that takes up this very question from the standpoint of the European climate movement in which he has been deeply involved. The title, How to Blow Up a Pipeline: Learning to Fight in a World on Fire, is designed to provoke. It does not literally explain how to blow up a pipeline, but it examines why asking that question shouldn’t so crazy.

Malm is a proponent of the following interconnected ideas:

The science on climate change has been clear for a very long time. Yet despite decades of committee appearances by scientists, mass street protests, petition campaigns, and peaceful demonstrations, the world is still facing a profitable fossil fuel industry, rising emission levels, and a rising temperature. With the stakes so high and 2C of warming effectively a point of no return, why haven’t more people considered non-peaceful protest?

If one accepts climate change is a genuine crisis (and more than enough people in the world have this view), then a form of revolution is necessary. Every route to revolutionary change in history has involved some level of property destruction as a means of rebalancing power.

Any kind of violence directed against people is wrong and completely disavowed. In saying this, the doctrine of ‘strategic nonviolence’ — associated with Mahatma Gandhi’s path to Indian independence, and Nelson Mandela’s work in 1980s South Africa, among other movements — has long prohibited vandalism or sabotage of property, and for the time and context of the climate crisis, Malm believes that’s not enough. Also the history taught to most of us in school of the most famous nonviolence moments in history (Gandhi, Mandela, Luther King) is deeply dishonest and inaccurate if it doesn’t acknowledge very significant components of physical confrontation with the prevailing order.

Movement orthodoxy is a common problem, especially on the Left. This means people usually become activists by turning up at meetings and hearing the methods and successes of others, which implicitly leads to many copied ideas. For the size of the climate danger, the climate movement is paltry in size, coordination, effort and imagination.

Activism if too polite is strategic pacifism. When unrestrained disorder is even threatened, such as in des gilets jaunes (Yellow Vest protests) in France through 2018-2019, then results follow. Climate activists should not abandon mass nonviolent mobilizations, but more escalated tactics should be part of the strategic mix.

The Left has been caught off guard by the scale of state intervention carried out to tackle the pandemic. The pandemic required enormous courage in government, to.. [effectively] “sacrifice the well-being of their capitalist economies for the lives of their elderly and potentially younger cohorts too.” Respect for private property and business continuity came second to the common good of ordinary lives, which should music to the ears of the Left, and show that more state action is possible.

SO IN A NUTSHELL, WHAT IS MALM ARGUING?

Malm is arguing there must an exception to the sanctity of private property if it relates to fossil fuels. An end to fossil fuels by definition means an end to private property in fossil fuels, because the firms won’t stop of their own volition. The most ideal scenario would be for the state to intervene, acquire and manage the transition in the public interest, but as they have shown no willingness to do so, ordinary citizens should demonstrate that private property is not sacred.

DON’T BE FOOLED…

The biggest mistake a reader of the above could make is to dismiss it outright. Malm’s writings are morally serious, and grounded in some compelling ideas that should make people who dislike its final message at least consider how he reached them.

BUT WAIT, WHY IS IT CALLED ECOLOGICAL LENINISM?

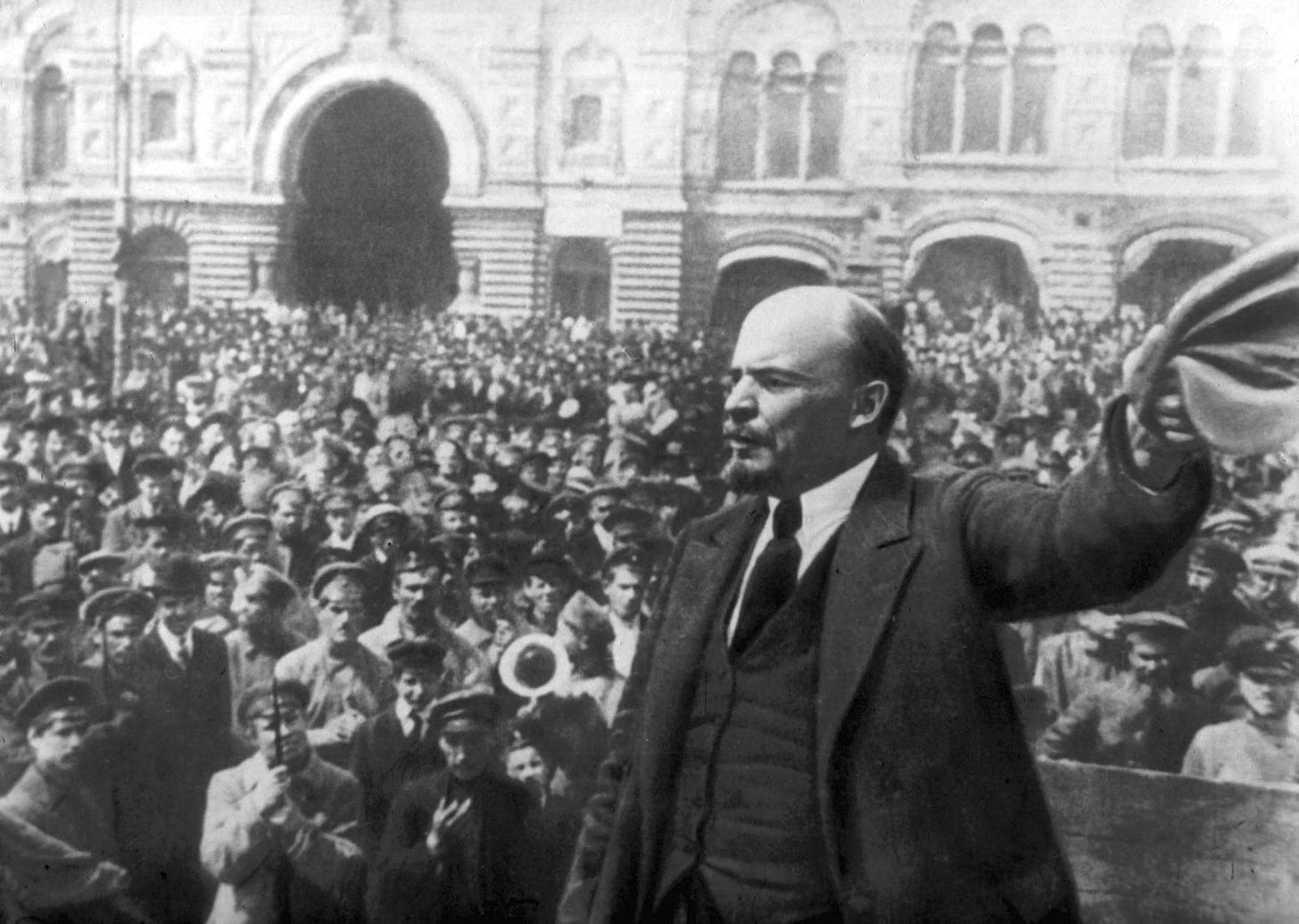

As far as branding goes, anything Leninist will land like a lead balloon in the United States from now until the end of time: but Malm’s use is strictly speaking, correct.

Lenin after 1914 was convinced the most significant event in world history was taking place around him, and it was his responsibility to shuffle the cards and turn World War I into a fatal blow against capitalism. He believed that in the fog of war, and with little to lose, people could be turned against money, inequality and a ruling class for good.

Unless you were a straight As high school student in Russian history, you’ll need reminding there was actually a civil war that followed the Russian Revolution of 1917. This pitted the Whites (who controlled much of the coal and oil areas of the country) against Lenin’s Red Army. The Bolshevik zone, confined to a modest stretch of the Russian empire, was desperately short of food, coal and oil. A harsh requisitioning system made it possible to feed the army, but a more innovative solution was needed to address the desperate shortage of coal. Cut off from fossil fuels, Lenin and Trotsky turned to wood. The Red Army’s armoured trains were fired with logs and against all odds, they succeeded against an opponent with all the fossil fuels at their disposal.

When Malm and others in his philosophical tree use the phrase ‘ecological Leninism’, they are effectively saying:

Revolutions will likely involve a destruction of private property, a fight for energy, and a seizure of state power if the state doesn’t do what you wish.

These ideas are often hard for activists (especially environmental activists) to embrace because they’re perennial outsiders, and often have a ‘state-phobia’.

Lenin asked his supporters, who’d also been lifelong outsiders, to seriously engage with the possibility of a ‘state-led, centrally planned, and global response’ to ending capitalism. Malm just wants the words climate crisis used in the end of that sentence instead.

In essence: there are industries necessary for large-scale decarbonisation, and they need to be nationalised. Malm is arguing for this as a strategic orientation, but in a new context: he wants the Left to find a way of turning the environmental crisis into a crisis for fossil capital itself, just as Lenin used WWI for the Bolshevik Revolution.

WHAT ARE SOME COMMON CRITICISMS OF MALM’S WORLDVIEW?

Critics argue one or any of the following:

Many utilities companies are already state-owned, yet they continue to be major sources of emissions. Doesn’t this show sector-wide state involvement is not a panacea?

Malm’s reply is public ownership is not a panacea in and of itself, but it makes the task of decarbonisation significantly easier. The advantage of having utilities under state ownership is that it allows governments to very quickly reorganize them. You do not need to first expropriate them or undertake the task of forcing privately owned companies to overhaul their current practices and leave fossil fuels in the ground. If the French government owned TOTAL or the British government owned BP, the transition could be more direct and consistent.

Doesn’t such increases in state power bring with it the danger of bureaucratisation and authoritarianism?

Absolutely, Malm is in no disagreement. But what is the alternative? Fossil fuel companies have so far done everything in their power to postpone and obstruct climate change mitigation, if their model of profiting from a ticking time bomb isn’t confronted, responses only become more drastic and extreme.

Doesn’t more radical action like destruction of private property risk alienating a moderate centre who are worried about climate change but don’t want to be associated with these tactics?

Malm counters that in his view there is no way forward from this present moment that doesn’t come with risks. He does concede in his book that it is probably worth giving the Green New Deal a chance first to be legislated over the next half-decade, and embedded in American politics like the Affordable Care Act in 2010, before moving to the next level of action.

Could a project with Leninist principles lead to a similar level of anarchy?

Malm rejects the Leninist doctrine of demolishing and replacing the state altogether. In his words: ‘all we have to work with is the dreary bourgeois state, tethered to the circuits of capital as always.’ That might be little comfort to most, but he is not arguing for the overthrow of capitalism (thankfully).

One thing to be said for Malm’s view: if it does represent the Far Left, it is blindingly simple. In this mindset, the problem with social democracy on the centre-left, or a liberal capitalist order on the centre-right, is that it has no concept of catastrophe — rather, it is premised on the opposite, namely the notion that we have time at our disposal and history on our side, meaning that we can move by incremental steps, have the centre-left and centre-right contest the middle ground, ride each boom and bust, alternate power, but in the long run always improve society. Malm argues this is a chronic emergency, and challenges his opponents to disagree.

If it’s accepted that this is an emergency, the political spectrum only offers two solutions—anarchism on the right, and his ideas on the left. Anarchism can’t coordinate a response to the climate crisis because it’s hostile to the state (by definition). Only large, coordinated state power can manage the transition required. And the Left should be accepting of this role, initially with targeted destructive action against fossil fuel property, and then involvement with the state in the seizure of assets so they can be transitioned out of production.

SO WHY ARE THESE IDEAS IMPORTANT?

Even if you or I don’t agree with Malm’s worldview (and some of you might, which is perfectly fine), we’re fast approaching a time where these ideas will have a lot of currency — especially for young people.

The difference between a 1.5C and 2C world is stark, and people under 25 years of age will increasingly view this step-change in global conditions as a point of no return (which let’s face it, it is). The WRI chart (below) released for COP26 in Glasgow is another sobering reminder.

Malm is aware that such tactics risk alienating support, inviting media denunciation and provoking massive repression. He is certainly hedging his bets, like all would-be revolutionaries: destroy property first which might be enough, but if it isn’t consider nearly everything after.

Lenin’s lesson to his supporters was that division and in-fighting were to be embraced, and never regretted. The prize of real change is too great. ‘Better to die blowing up a pipeline,’ Malm concludes, ‘than to burn impassively.’

What’s chilling is less the idea on its own, and more the reality that we can all visualise this being taken literally by someone in the not too distant future.

These ideas are important for a Climate and Money audience to be aware of, because more radical options like this will become palatable for enough people if financial markets fail to come good on their bargain of managing the transition through capital transfer, shareholder activism and new regulations alone.

A time will likely come where school strikes and UN conferences have not achieved their intended aim, and there are only big risks and revolutionary options. Hopefully it doesn’t come to that.

Optimistically,

Owen C. Woolcock

3 Questions I Am Asking Myself This Week

1. Some cause for hope!

2. This was the front page of the Australian Financial Review two days ago, and what fossil fuel executives woke to. What did the public make of it, and what were Google’s search results for green hydrogen that day?

3. Polymath Tyler Cowen’s question in his excellent Bloomberg article this week is a thought-provoking one..

If You Read Or Listen To One Thing This Week

A fascinating podcast discussion from Energy vs. Climate on how what it will take to decarbonise aviation.