#18: What Is The Right Value For Water?

If you go deep in any point of human history, it can be terrifying how pivotal water security is to any civilisation. Today is no different. But the fragility has new market-oriented dimensions.

PRESSED FOR TIME?

A small town running out of water in Northern California takes us to a deeper question: what’s the value of water when it’s abundant, and what’s the value when it’s disappearing? This issue sheds light on three important questions around water risk, and leaves us with the sober reality that market forces and individual scarcity are likely to lead to less of what we’re used to, and more of what we need.

A TOWN FROM A BYGONE ERA

On the California coastline, there’s a small town you’ve likely never heard of, called Mendocino. A misty, forested beachside town, Mendocino is a timeless Northern Californian enclave, with a surprising detail in plain sight.

Despite being nestled along a number of major rivers, creeks and springs, the town of just 1,000 residents—but double that number of tourists each day in the summer—relies on a network of 420 wells rather than a centralised water system.

WAIT: they literally lower buckets into wells like medieval times? Not exactly.

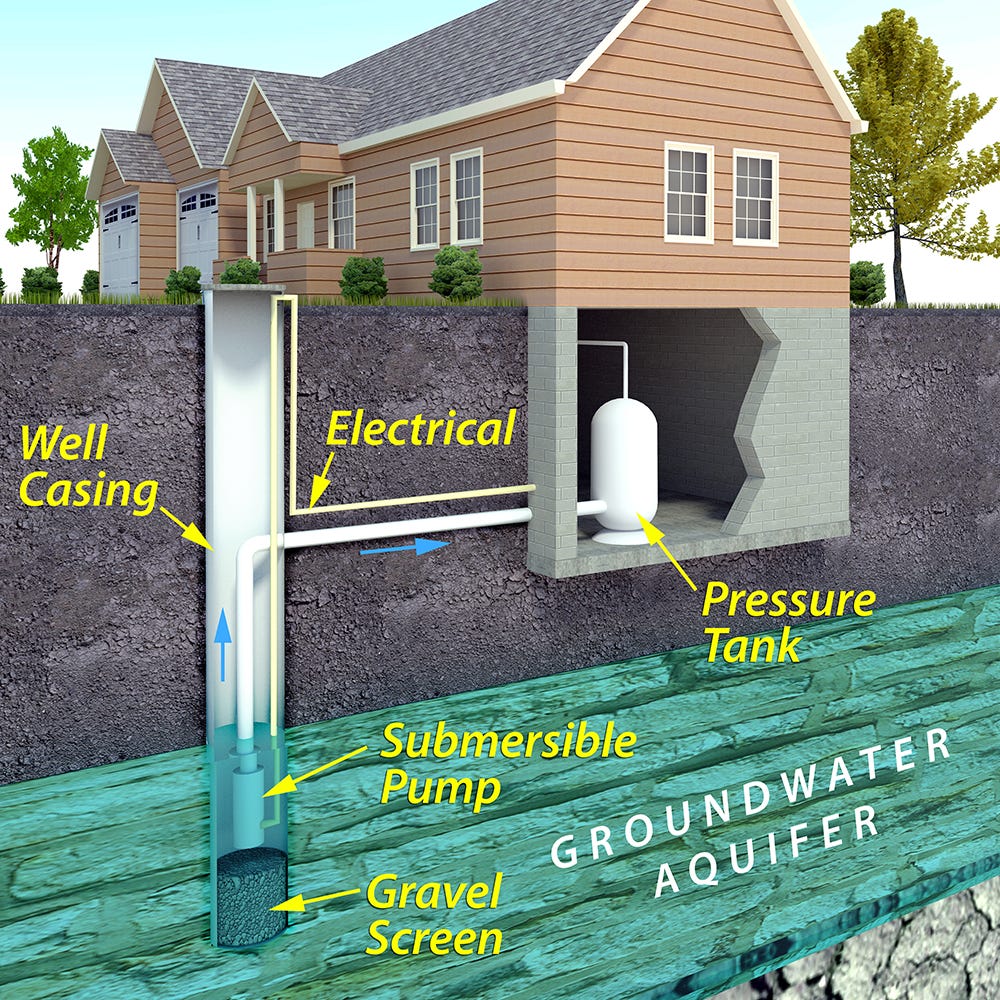

Well water is untreated groundwater stored in aquifers (underground layers of porous rock). Wells get drilled as far down as 1,000 feet into the rock to access the water. Pipe casing gets installed into the hole, and a concrete or clay sealant surrounds it to protect against contaminants. Water travels through this casing via a well pump. The well system gets capped off above ground. The water then enters the home from a pipe connected between the casing and a pressure tank (generally located in your home’s basement). From there, it gets distributed to faucets throughout your home.

Well water is more likely to be hard water, meaning that it contains minerals like calcium and magnesium. Water containing minerals can be a good thing. Still, too many minerals can create build-up in pipes and heating systems, leading to costly repairs. Hard water also performs poorly with soaps and detergents, leaving spots on dishes, shower doors, and generally not cleaning things as well as soft water.

Water coming from your well is also more likely to encounter other contaminants. Depending on where you live, iron, sulfur gas, arsenic, nitrates, tannins, and various other items found in nature could be present. Some parts of the United States do not have iron issues. In contrast, other areas might have entire neighborhoods with whole-home iron filters to prevent rust stains from forming on everything their water touches.

So wells have some challenges, but with the right technology still can represent a functioning water system in a 21st Century community.

As you can imagine given California’s second full year of drought, there’s a problem. Over 100 of the wells in Mendocino are dry, or close to dry.

Would this worry you if you were a local citizen? It depends on your viewpoint. Some might think 100 dry wells out of 420 as no different to a dam at 75% capacity. Others would be concerned that aquifers have long-term water-level declines caused by sustained groundwater pumping, and know this is a resource that’s expensive to recharge.

Another concern for Mendocino is help is not on the way. Fort Bragg, a nearby city that has served as a backup source of water in the past, can no longer send water because it’s worried about its own supply. Willits, another nearby town, has said the same thing. Why has Fort Bragg been less generous? High tides have pushed brackish water up the dwindling Noyo River, which Fort Bragg relies on for its water, and local officials decided to stop outside sales to protect residents’ supply. As we see so often on Climate and Money, climate risk is typically actors managing and prioritising overlapping threats.

With neighbouring towns unable to help, the cost of deliveries continues to increase as trucks have to travel further. Because these surrounding areas are also facing shortages, the costs of getting tanker trucks full of potable water has nearly doubled over the past few months—from about $350.00 per 3,500-gallon load to $600.00.

What does this mean on the ground? Two of the best restaurants in town and the local grocery market have closed restrooms, and brought in portable toilets. Elderly residents take ‘navy showers’ with the tap turned off during shampoo and soap lathering.

TRENDS REFLECTING A BROADER WORRY

These problems aren’t confined to Mendocino. Lake Tahoe water levels have hit a four year low, as the drought continues to ravage California. Governor Gavin Newsom asked the population to cut water usage by 15%. And in August, California water regulators voted unanimously to stop diversions from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, a vast watershed sprawling from Fresno to the Oregon border. What are farmers expected to rely on after this unprecedented action? You guessed it: groundwater wells.

From the snow-capped Rockies to the flat expanses of the prairies, and from the wetlands of Florida to the deserts of Arizona, the U.S. is a country of geographical extremes with rainfall patterns to match. Louisiana gets over 60 inches of rainfall a year, while in Nevada, less than 10 inches of rain falls annually in valleys and deserts.

WATER 101

But you’d be right to ask a few basic questions, given the vastness of the topic beyond California’s present situation:

How important is water to a human being?

What is the price of water in the different forms we consume it?

What is good, bad and unusable water?

How are financial markets trying to address this challenge?

First, the basics. Humans survive approx. 3 days (or 72 hours) without water: it’s basic physiology—your wealth, power and financial influence matter little in this simple arithmetic. Most water we use goes to agriculture. It is the sector that places significant pressure on the world's fresh water, accounting for nearly 70% of all water withdrawals. That number can rise to more than 90% in countries like Pakistan where farming is most intensive, and has little mechanisation or innovation.

Secondly, the unpleasant reality of the human lottery. Some 2.1 billion people do not have safe, affordable, and accessible drinking water, and more than 4.5 billion lack sanitary toilet facilities, according to the UN. Given the global population is 7.9 billion, another way to think of this is if you flipped a coin just four times, there’s a 25% you would end up one of those people drinking dirty (or toxic) water.

The funny thing is water can be incredibly cheap in wealthy nations too. The average cost for monthly water usage in Florida is just $6.00, but the average monthly cost in West Virginia is $72.00. Does this surprise you? Water definitely has what’s known as a pricing paradox: it almost never equals its value and rarely covers its cost.

Thirdly, there’s the science. Climate change influences the availability and quality of water resources. On a hotter planet, extreme and irregular weather events such as floods and droughts are becoming more frequent. One reason why is that a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture. Existing precipitation patterns are expected to become entrenched. Dry areas will become drier, and wet areas wetter.

Water quality is changing, too. Warmer river and lake temperatures reduce dissolved oxygen and make habitats more lethal to fish. Warming waters are also more prolific incubators of harmful algae, which are toxic to aquatic life and humans (NB: this is a big risk in places like Lake Tahoe).

We could summarise this dilemma in the following way: bad and unusable water is going to increase, and good water is going to demand a higher price.

HOW IS THE MARKET RESPONDING?

One hardware response being used in Mendocino is GoSun, a company that sells off-grid tech and now distributes machines from Tsunami, one of a handful of manufacturers that make air-to-water units. ‘The machine draws in fresh ambient air through a filter, and that filtered air passes through another compartment where we have a condenser coil to chill the air,’ says Ted Bowman, a product developer at Tsunami.

In the same way that an air conditioner creates condensation, the system pulls drips of water out of the air, and then collects it in a basin to filter and purify it. “We’re basically doing the same thing in nature as a cloud does, but we’re trying to do it mechanically,’ Bowman told Fast Company in a recent story.

A small machine can produce around 180 gallons of water a day—more than an average home needs—under optimal conditions of 80% humidity and 80 degree weather. Mendocino isn’t typically hot, but it is foggy, which can help the system work well. It’s not cheap however, with a unit running around $30,000.

HOW ARE THE MARKETS RESPONDING?

In the financial markets, innovation is occuring. A firm named Thomas Schumann Capital has created, sponsored and launched the TSC Water Security Index, the world’s first benchmark index quantifying water risk in equities and the first-ever water footprint for global capital markets.

What is TSC really seeking to price? The extent to which the companies around us each and every day are thinking about water risk, and managing their responsibility to use and conserve wisely.

How well does a company use water?

What is their total water withdrawal?

What is their fresh water withdrawal?

What is the amount of water discharged or recycled, and what pollutants associated?

Do they have water policies arcing toward greater efficiency over time?

These are not simple questions to answer: consider any half-dozen listed companies in the S&P 500 and imagine the challenges of retrieving accurate data? 594 of the 600 largest US companies report some or all water measures, but harmonising and comparing apples to apples is not easy.

Most existing Water Funds are focused on water purification manufacturing and water utilities. Existing water indices are also highly concentrated (typically 30-50 companies) and invest solely in equities that are in the water industry (manufacture water purification/recycling products and water utilities.) Their scope provides less diversification, scalability and no measurement of water risk. TSC’s Water Security Fund (and a looming ETF series) provides a very interesting and important entry point for those thinking about the ways markets can force water stewardship at the economy-wide level.

CAN WATER INTERESTS EVER ALIGN?

This issue has touched on three different perspectives of an enormous topic:

What is the risk water runs out where I live?

What are the technologies needed to find water where it’s getting worse, unusable or needing to be retrieved in new ways?

How can ordinary retail investors push for better water stewardship from the largest companies in the world?

No question can be answered simply, and nothing overcomes the reality of the science. As temperatures warm, evaporation increases, further decreasing water in lakes, reservoirs, and rivers. As one example, every degree of warming in the Salt Lake City region could drop the annual water flow of surrounding streams by as much as 6.5 percent—for cities in the western U.S. that rely on cool temperatures to generate snow and rain, warmer weather is bad news.

As the U.S. water supply decreases, demand is set to increase. On average, each American uses 80 to 100 gallons of water every day, with the nation’s estimated total daily usage topping 345 billion gallons—enough to sink the state of Rhode Island under a foot of water. By 2100 the U.S. population will have increased by nearly 200 million, with a total population of some 514 million people. Given that we use water for everything, the simple math is that more people mean more water stress across the country.

That means more people waking to less of what they had, more technology proving popular to try solving this issue, and more investment vehicles needed to separate early-mover public market actors from those continuing to use water like it’s abundant and nearly free.

In different ways, all three are probably a good and necessary thing.

Optimistically,

Owen C. Woolcock

3 Questions I Am Asking Myself This Week

1. When will FEMA Risk Rating 2.0 drop, and how big might the fallout be?

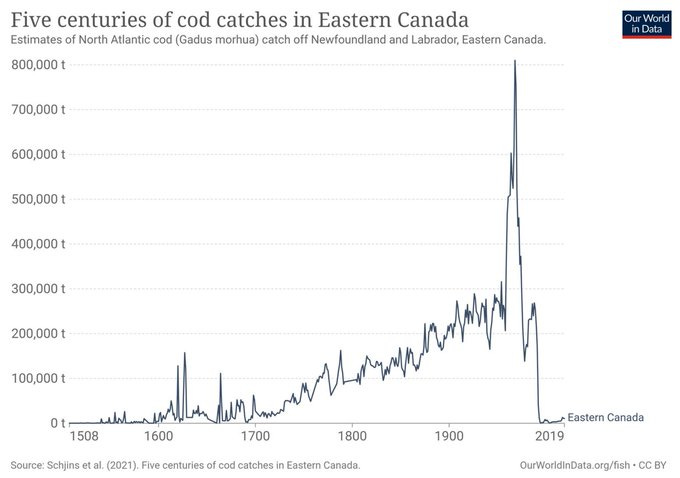

2. If anyone ever wants to see an example of ecological systems with multiple equilibria, look no further than the Canadian cod fishery system.

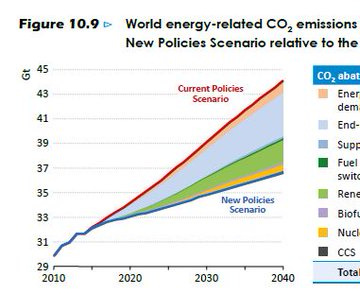

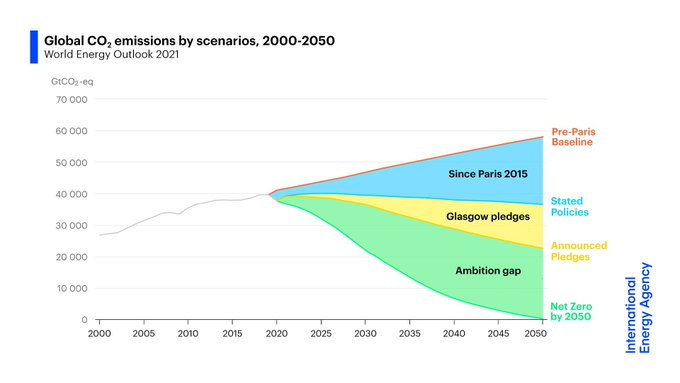

3. On a brighter note to finish! If anyone wanted to feel relieved by the importance and momentum of the Paris Agreement in 2015, consider the International Energy Agency's annual CO2 emissions projection for that year (top) and the same figures in 2021 (bottom). Staggering progress in a short time, IF the pledges are kept.

If You Read Or Listen To One Thing This Week

A powerful VICE News video on the disappearing bark beetle and an ecologist who finds herself documenting species death as much as life.