#17: When Should You Evacuate, And What Is The Cost?

The aftermath of Hurricane Ida in the American Gulf Coast and Northeast took the headlines, but we need to examine a very important story that unfolded as the storm was building.

PRESSED FOR TIME?

Hurricane Ida's damage bill could top $95 billion, making it the seventh costliest hurricane in the U.S. since 2000. But a worrying new trend is emerging with climate change, namely the speed that high-severity storms outpace the speed large metro areas can mobilise a full evacuation. This issue puts you at the centre of a major storm warning, and asks: when would you stay, when would you go, and what is the cost involved in the tradeoffs?

For a slightly different format this issue we’re going to put you, the reader, on the ground in New Orleans, Louisiana (NOLA) on Thursday, 26th August 2021, and lay out information that came to local residents. If you’ve never been to New Orleans, it’s just as instructive to imagine for a few minutes that you live in any coastal city with a meaningful storm risk. Transplant your own real-life situation to that moment: imagine you’re a renter or homeowner, with a job, employment commitments, get-togethers planned, and perhaps a young family.

And then a neighbour or news flash tells you there’s a storm coming.

THURSDAY 26TH AUGUST: 0900hrs CT

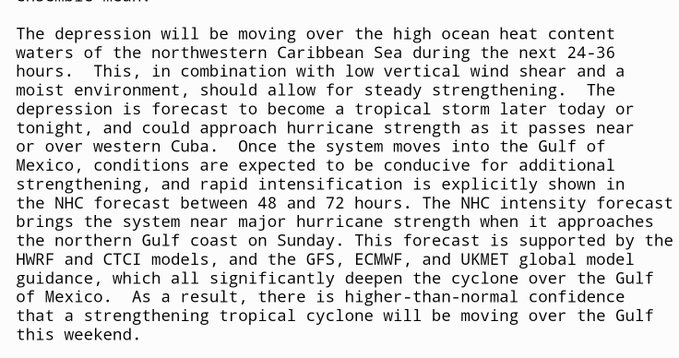

From the first advisory of Tropical Depression 9, or TD9 (pre-Ida) on Thursday morning, it was abundantly clear this storm presented a huge threat to the northern Gulf coast on Sunday. As the image below shows, it is rare for projections to be this tight, as hurricane modellers like to say.

A direct hit from a major hurricane stirs deep and difficult memories for NOLA, given the events of August 2005 when Hurricane Katrina forced levee failures that flooded 80% of the city and left over 1,800 dead along with $125 billion in damages.

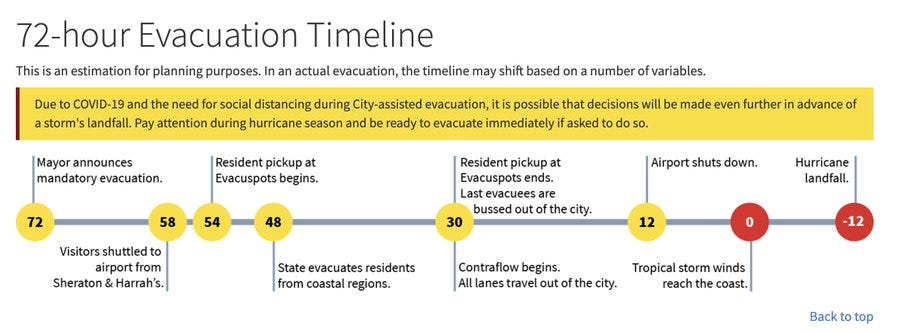

On the Thursday morning, with the tight projections, what should NOLA officials do? Any decision to evacuate must ensure the full evacuation has taken place before the first arrival of tropical-storm winds in Louisiana — that’s when drivers need to start getting off the roads, and when local services are shut down until the storm passes.

Calling for widespread evacuation is no light decision. Many storms have called for evacuations, and the storm missed the city. This occurred with Hurricane Ivan in September 2004, a now largely forgotten storm that many predicted would hit NOLA and swerved right — in fact, many believe the recency bias of Ivan played a role in the decisions of some NOLA residents in the lead-up to Hurricane Katrina the following summer, in 2005.

NOLA planning timelines, at least as of 2020, required 84 hours (or 3.5 days) before landfall to evacuate the city. Unfortunately Hurricane Ida didn’t give that amount of time. While it was a well-predicted storm, 60 hours of warning was too short for NOLA officials to issue a mandatory evacuation order in the days before it landed.

Here we run into a fundamental problem of math. Most major hurricanes get to be major via rapid intensification, and so a weather agency is unlikely to ever get 3.5 days warning to pass onto the public.

WHAT ARE WE SOLVING FOR?

We also need to ask what officials are solving for? Is it the big one, and averting as much death and destruction as possible? Typically the more serious a hurricane, the more damage and risk of fatality. Over the past few decades, meteorologists have gotten significantly better at predicting where a storm might go, but they still don’t always know how strong it will be when it gets there. That’s a problem, because decision makers need to know both track and intensity to make good calls. Knowing a storm will pass overhead in three days is meaningless if you don’t know whether it will be Category 1 or Category 5 when it arrives.

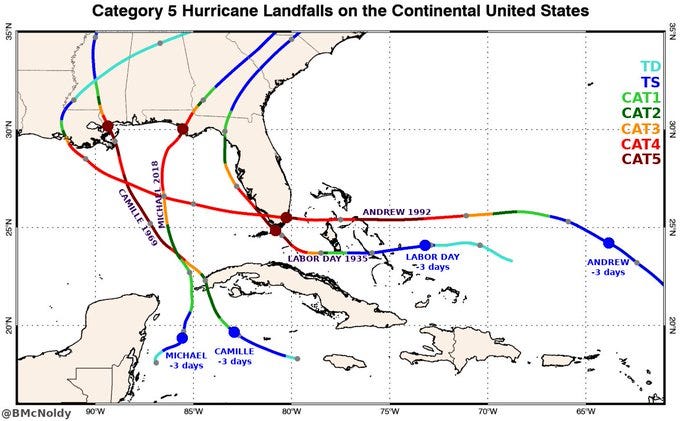

For those not well versed in hurricane modelling, it’s worth mentioning that ALL FOUR Category 5 hurricane landfalls on the continental U.S. — yes, just four — were just tropical storms three days prior. So the evacuation warning of 72 hours gives little protection from the very worst.

So shouldn’t the default position be to evacuate? It might shock you to learn more people died in Hurricane Rita's (2005) evacuation in Texas than from the storm itself.

SO WHAT DO YOU DO?

Let’s return to that Thursday morning, and your decision with a house full of possessions, a job, partner and (perhaps) children. No mandatory evacuation has been issued, it is up to residents to make their own decisions. There’s still two days of the working week, so why not stay, keep monitoring the storm, and leave Saturday morning if it continues to look ominous. It turns out this was the logic of many in NOLA, who left it to Saturday to leave for a Sunday storm.

Imagine the worst traffic you’ve seen around your neighbourhood. Then imagine the entire city you live in trying to leave over a 24 hour window.

You’ll see a word in the above graphic that you might not have seen before: contraflow. This is a phrase to describe when all roads (highway and non-highway) face in one direction, to enable a rapid exodus. The below is a photo from FOX8 NOLA news coverage, showing the bottlenecks that existed Saturday, largely because contraflow was not implemented. What was the city’s reason for not enacting it? From their perspective, Ida intensified too fast to allow a mandatory evacuation, and all the detailed planning that contraflow required.

The chances are you’ve likely read this, and made a natural assumption from the above information: you have a car to evacuate. Many don’t.

When Hurricane Ida approached, seven retirement homes in the NOLA area were evacuated, and 843 residents were brought to a warehouse facility on the Friday. After landfall Sunday, backup generators failed, trash piled up and care declined to shockingly poor standards, with residents complaining of having to lie in their own faeces and urine. By the Thursday after Ida had passed, four residents had died.

Then there’s the poor and immobilised. As the NYT Daily illustrated with the story of the largely black complex in New Orleans East called the Willows, stories ranged from unemployed black men who had their cars in the parts shop for new tyres, and no cash flow to get the repairs done so they could leave, to matriarchs of large black families with multiple children and grandchildren with disabilities, making it impossible to leave without taking everyone.

And if they left, where do they go? Hostels in Baton Rouge or other refuge towns cost money, which often come off the next month’s rent for someone close to the poverty line. But by staying, there was no guarantee of groceries being open, trash or water services staying on, or life coming back to normal for weeks. NOLA officials try to bus out many people at ‘evacu-spots’ but for the reasons above, many don’t want to go.

So when you reflect on the original news, would you have left Thursday, Friday, Saturday or not at all?

SUNDAY, 29TH AUGUST: 1800hrs CT

With wind speeds of 150 miles an hour at the moment of landfall, Ida—which eventually weakened to a Category 3 storm—was both a better outcome than dreaded, and a terrible storm regardless. While the extent of damage in the most affected areas is still unclear a week or so on, the storm caused catastrophic power loss in New Orleans and forced doctors and nurses in at least one hospital to pump air into COVID-19 patients’ lungs by hand. It also knocked out 95 percent of U.S. oil production in the Gulf of Mexico. So in your own personal decision tree, where were you — a few hundred miles away, or stuck back in town?

THE AFTERMATH

The weeks after provided very little sense of celebration, even if the $14 billion levee system averted any Katrina-like repeat of NOLA being flooded. There’s been no electricity and no air conditioning in much of the city, and in late August in south Louisiana, it’s sweltering — with the heat index regularly above 100F. Lines for gasoline can stretch for four hours. People don’t have jobs to go back to, the schools are closed, and so the entire city sits in an odd stasis, while excess heat deaths rise (89 deaths in Louisiana since Ida from heat stress at the time of publication).

Some levees still failed in neighbouring areas (or parishes as they are known in Louisiana). The most notable failure was in the town of Lafitte, just south of the city. As Ida rolled north, a massive storm surge of 12 feet overtopped the ring of seven-foot-tall levees that surround the town of around 2,000 residents, inundating almost every home and business. The town’s locally maintained levee ring, which was the product of a sustained lobbying campaign by local leadership, had been completed only last year and had been intended to attract long-term investment to the small shrimping town. Ida revealed in the space of hours that the town was much more vulnerable than engineers had assumed. At its peak, the storm surge was almost twice as high as the levees that were supposed to contain it. So here was a town that tried in good faith to stem the retreat of investment we so often talk about on Climate and Money, and nature still had the final say.

Knowing all of this, would you have stayed? And if you’d have left, when would you decide to return?

HOW IS CLIMATE CHANGE AFFECTING HURRICANES?

So how much of this is climate change, and how much the challenges of time-honoured hurricanes? Climate change has a subtle influence on hurricanes. They seem to be getting wetter and more intense, but not necessarily more frequent. Scientists are confident that global warming is increasing rainfall from major tropical cyclones, just as it is increasing precipitation amounts from all types of storms. Some researchers also believe that more hurricanes are following the pattern taken by Ida and getting significantly stronger in the hours before landfall.

Ultimately, we keep coming back to the same conundrum: it’s not going to be the past, and our cities, planning conditions and real estate markets are designed for a car-oriented century and a kinder, more stable climate.

CONCLUSION

If rapid intensification becomes more common, then officials will find it harder to make good judgments about hurricanes. It now takes longer to evacuate a city than it does to build a destructive hurricane. And that leaves anyone in a hurricane path with limited information to make some of the most pivotal decisions imaginable. Even when the storm hits, there are points of failure for which no one can be certain about the recovery timeline. Finally there are those without the means to evacuate.

As the pandemic and Hurricane Ida have shown, one of the hardest things to price is the cost of a non-zero probability. What if Ida had petered out to a regular storm? What if had been the fifth Category-5 Big One? Asking what level of caution or confidence you might’ve taken in the shoes of a New Orleans local three weekends ago is an important, if uncomfortable, question.

Optimistically,

Owen C. Woolcock.

3 Questions I Am Asking Myself This Week

1. Local energy provider Entergy recorded the number of poles broken during Ida compared to hurricanes in the past. It’s captured in this graphic below. Who really pays for this, and what is the long run cost?

2. Around 30 billion gallons of water fell across the five boroughs of New York during the storm remnants of Ida. If someone could drop that much water on the California fires it would take 1.5 million separate water drop flights from a 747 Supertanker.

3. Ida has stolen most of the headlines, but the wildfire situation in California continues to be quite serious. Here's an updated Top 20 list for the state, courtesy of catastrophe modeller Steve Bowen. Three 2021 fires (Dixie, Caldor, Monument) sit in the Top 20 largest fires since 1932:

If You Read Or Listen To One Thing This Week

We will likely cover Ida’s impact on New York and New Jersey in a future issue, but if you missed the dramatic scenes around Manhattan, this is a nice collage of videos from the New York Times.