#14: What Does the IPCC Report Mean for You, Me and Investing?

The IPCC AR6 Report shows there is little time left to avert the worst, but alongside political action, it matters where we invest.

PRESSED FOR TIME?

The climate science and policy world is timestamped by the release of each IPCC report — a major piece of scholarship review that allows the world to take stock of its progress (or lack thereof) in the battle to decarbonise and prevent dramatic climate change. It’s big, good work and deserves attention. The common focus is on the scary prognosis for this century, but this issue will examine what it means for financial markets and investment runways.

WHAT IS THE IPCC REPORT, AND WHY DOES IT MATTER?

When the scientific community realised the scale of the greenhouse effect in the 1980s, there needed to be a way to monitor and report back on new information as it arose. The IPCC is the body of the world’s leading climate experts, formed in 1988 and charged with preparing comprehensive reports on the state of our knowledge of the climate.

Its first report in 1990 warned of the potential consequences of rising greenhouse gas emissions, and was key to the forging two years later of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the parent treaty to the 2015 Paris agreement.

Since then, reports have been produced roughly every seven years. The IPCC is now in its sixth assessment cycle, which is why you see the acronym AR6 for the Sixth Assessment Report. Only the first part, dealing with our knowledge of the physical basis of climate change – the core underlying science – was published on Monday. Two further instalments, on the impacts of the climate crisis and on ways of reducing those impacts, will follow next year.

Exactly 234 scientists from 66 countries have put in five years of effort to understand and report on climate change and its global impacts. I’ve had the privilege here at Harvard to work with, or study some of those who’ve been involved either in submitting papers, or reviewing the science. For those who spend a lot of time away from the peer-reviewed research method, I say with what integrity I have that it’s an incredibly demanding process. That’s why it deserves our attention, even if only for a one week media cycle.

HOW BAD IS IT?

Catastrophic is not a light word to use. If you feel like going deep on the conclusions, and/or getting depressed, check out excellent summaries here, here and here.

Alternatively, you could look at this photo taken from Greece last week during their extraordinary fires, and remind yourself that in many ways, we’ve already entered something verging on the surreal. How poignant, and unsettling that the only person looking at the camera is a young child.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR MONEY?

At Climate and Money, we’ve always been focused on bringing two worlds together: two audiences — climate science, and ordinary people with relationships to the markets — who need to understand the other’s language, outlook and incentives. The internet is filled with responses from the IPCC’s update that are rightly despondent about our ability to avert the worst of our possible futures.

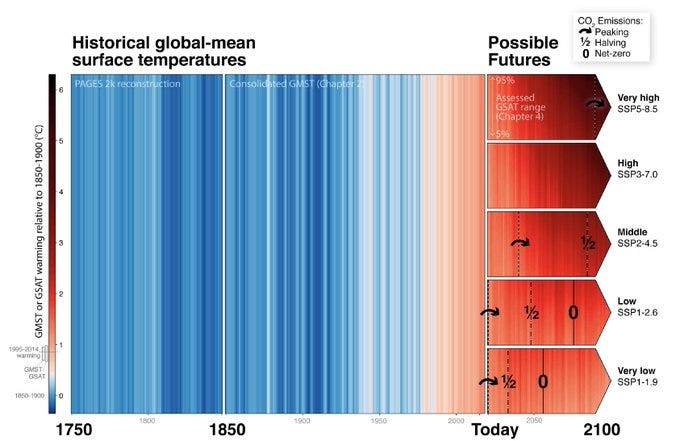

As a refresher, this excellent bit of data visualisation from the report itself shows the pathway of global average surface temperatures we’ve been on, and our five options (and they are options in that choices are involved). The cheat sheet notes are this: we have to be in the bottom three boxes, and have the ‘peaking’ arrow as close to today as possible, which brings the ‘1/2’ and ‘0’ lines closer, thereby keeping global temperatures to a tolerable level. Only the bottom box gives us a chance at having a planet anything like what we know, and even that’s technically a stretch to say.

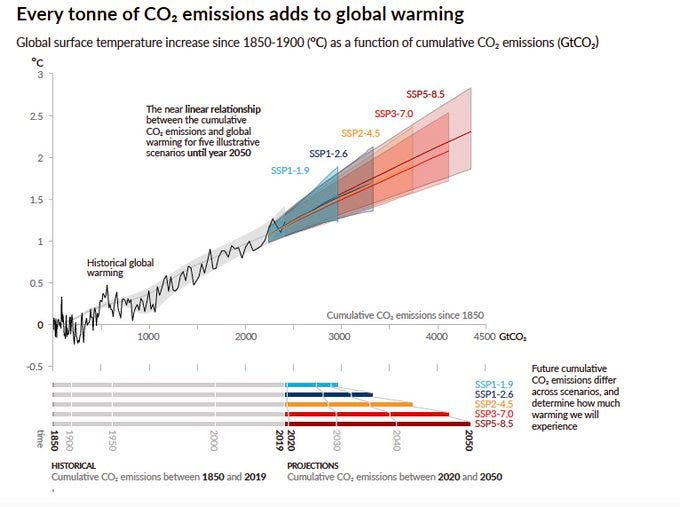

How can our actions in one lifetime have so much significance, you might ask? Surely we’ve been emitting fossil fuels since the 1850s? Well partly it’s the carbon budget, covered in a recent issue, which shows we’ve exhausted the allotment before the impacts started to be severe. But the other critical part is unlike conventional air pollution, which eventually ‘goes away’, most of the CO2 we emit stays in the atmosphere for hundreds to thousands of years. Its impacts are cumulative, which is why every tonne of greenhouse gas matters.

This is why there is a time-value to emissions reductions.

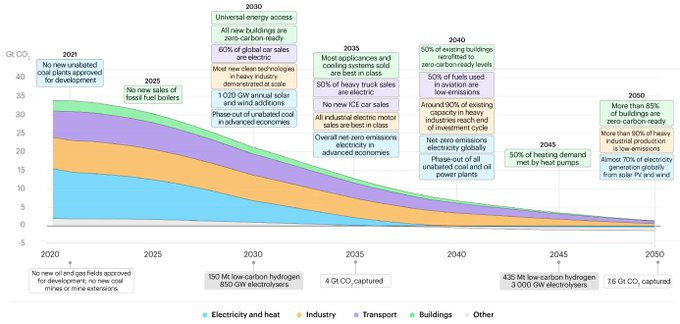

Breakthrough technologies to greatly accelerate emissions reductions are important. But also, every year we don’t implement available solutions is another year of carbon budget lost. With no time left, we now need to do the available solutions AND invest in breakthroughs. The change in our economy will be significant. This excellent timeline released by the International Energy Agency (IEA) shows what needs to happen and when.

If you take nothing else from this issue, look closely at the timeline above and ask: am I investing in firms that will take advantage of this multi-phased industrial transfer?

A lot of this is around revisiting assumptions. So let’s look at two domains where we might see a need for new dollars, and outsized returns for those who understand the enormity of the opportunity:

1. THE SPATIAL PATTERNS OF REFUELLING

A WSJ article this week on gas stations pointed to an interesting reality of owner/operators in the built environment, given the spatial patterns of how we refuel vehicles: gas stations will become a stranded asset — people will stop building them, even before they become completely unviable — because they anticipate declining future profits.

As the story shows, some gas stations, convenience stores and truck stops in America are adding chargers to test the technology and protect their market share for the long run. This is intuitive. Others say they crunched the numbers and decided they can’t justify the cost, given the small share of electric-vehicle (EV) drivers. Charging units and installation typically cost upward of $100,000 each, and might entail the expense of tearing up pavement to lay conduit.

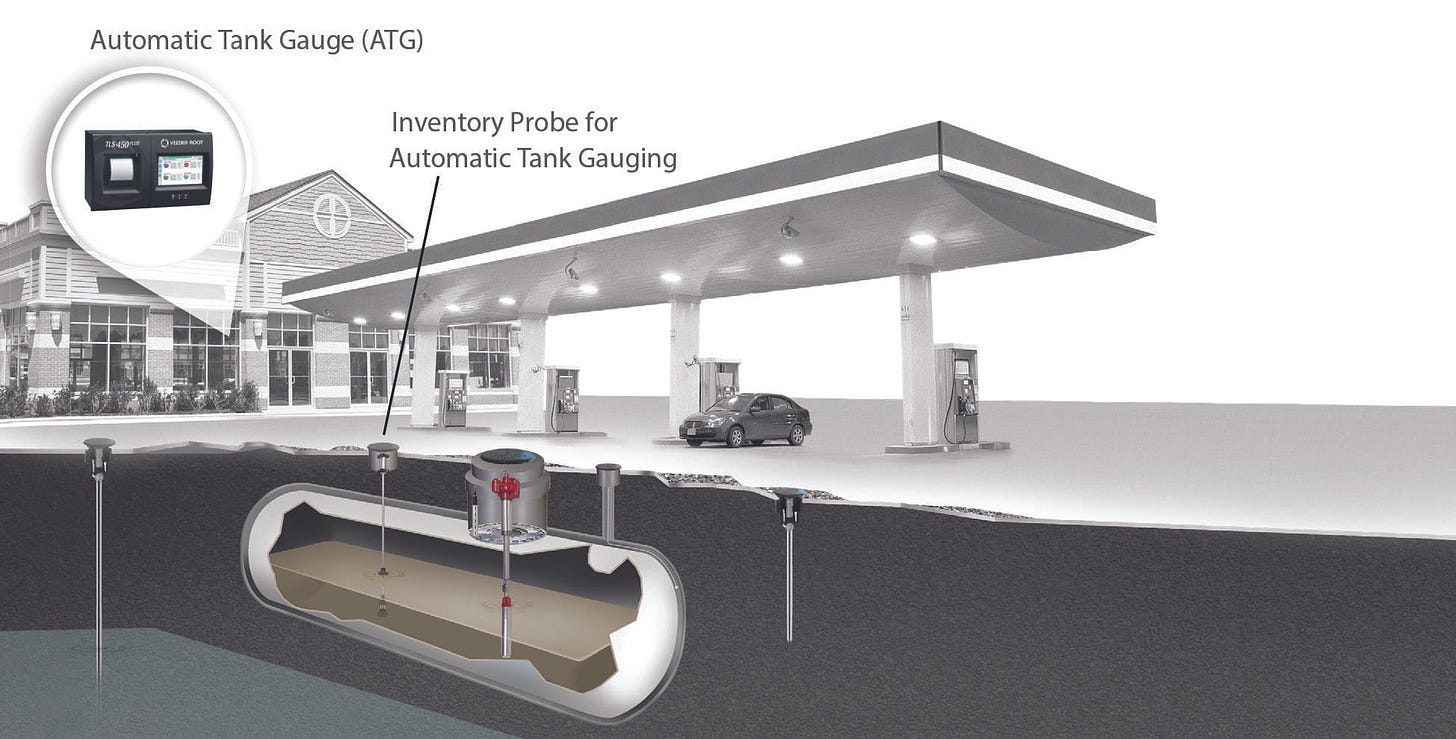

This begs the question: have you ever wondered how your nearby gas station works? The normal range of capacity in the U.S. is 10,000-12,000 gallons per pump, stored in underground tanks. The metal tanks used in days gone by failed in short order, anywhere from four or five years to twenty or thirty years as a rule. Today’s modern tanks use synthetics that don’t rust or don’t break down when in contact with gasoline, and can last a century. This is a long investment cycle.

So what is a husband and wife franchise owner of a gas station seeking to achieve with a few GM EV charging stations? This is a perfect example of the uncertain middle zone: are hard capex investments worth it?

Then there’s the reality of how EV manufacturers are planning to enter the market: they want to control the experience. Examples like this Tesla supercharger facility show the totality of throughput, the focus on aesthetic, the solar panels a standard of site base load generation. Also one needs to factor in that EVs will be adopted in wealthier areas at a faster rate: what does that do to the balance of standard fuel vs. EV charging options in some parts of cities?

But let’s not forget the IEA’s explicit goal in the their timeline above: 60% of all global car sales being electric by 2030. As the IPCC Report showed, that’s non-negotiable. The next time you drive past your local gas station, take a look at the lot size, the entry and exit points, the retail parking, the socio-economic level of the area, and ask: how will that site manage this transition? What products and services will address new market needs, and what will happen to the real estate on or around that site as these needs change? There are more than 150,000 fuelling stations across the United States, with 127,588 of these stations convenience stores selling fuel. In a small domain of modern life, we’re about to see a huge opportunity for growth if the right firms are identified.

2. THE CLEANING INPUTS NEEDED IN EVERYTHING

A Boston angel investor and early stage climate fund this week announced funding for Remora, a startup looking to make a big impact in long haul trucking.

Of the 6.6 billion metric tons of CO2 emissions generated each year in the U.S., nearly a third comes from transportation and, within that segment, 23% comes from medium and heavy-duty trucks. That’s 6.8% of total emissions in America.

Trucking requires custom solutions in order to reduce its carbon footprint. Even with big battery breakthroughs, electric vehicles will probably never be a practical solution for things like 18-wheelers.

At the company’s Detroit, MI facility, Remora has been retrofitting semi-trucks with their proprietary carbon capture technology. The hardware is installed between the truck and its trailer, where it attaches to the tailpipes of the vehicle and captures its carbon emissions.

Remora plans to establish CO2 offloading sites at distribution centers and truck stops, where captured emissions are pumped and stored in tanks. From there, Remora picks up the CO2 in a tanker truck and permanently stores the CO2 underground, which it can then monetise through tax credits and the sale of carbon offsets. In the short term, Remora plans to sell CO2 to concrete producers and other businesses that use it as input.

This video summarises their efforts well:

This is the image I think is worth reflecting on:

In the space of a 53-feet long structure, weighing up to 33,000 lbs, someone realised the space for an input that no one else had (black inset). This is likely to be the story of reaching net-zero, seeing the imaginative that looks obvious in hindsight.

It’s worth each investor asking: where else is this likely to occur?

A FINAL THOUGHT, WITH A DIFFERENCE

It would be flippant to not return one last time to the scale of the IPCC’s forecast. Being a parent brings into sharp focus the implications of the change we need to see. In that vein, I wanted to share a slightly unconventional final thought —

A few years ago I read a short novella called The Last Children of Tokyo, by Yoko Tawada. Set in a dystopian future where an unspecified global catastrophe has plunged the world into chaos, cities become unsafe due to air and water pollution. Over the preceding century, successive generations of children have been born increasingly feeble and prone to illness, so that while the elderly continued to live with undiminished vitality, children in each generation were increasingly intolerant to most foods, with malformed teeth due to lack of calcium, and severely deformed bones.

The book has just two main characters: Yoshiro, fit and spritely at over 100 years old, and his great-great grandson Mumei, who is in second grade. All the generations between are no longer alive, with life expectancy collapsing for descendants in Yoshiro’s family line. Mumei, and a handful of others around his age attend school but are unlikely to live beyond their teens: for that reason, they are the last children of Tokyo.

The most painful, and evocative analogy from the book was of Yoshiro running four-minute miles beyond 100, and pushing his great-grandson Mumei in a stroller along the polluted waterways on the outskirts of the city. The power of the author’s vision was to construct a world where an old generation had all the bounty of nature, but were condemned to watch every generation after them lead poorer lives in every way. Their fitness and recollections of the world before the catastrophe worked together to make their lives long and regretful, never able to restore what they took for granted, and never able to see their descendants flourish.

If one is inclined, there’s plenty of dystopian climate fiction to read. If you do, it’s easy to get despondent. But if you take one central idea from the IPCC Report this week, as someone coming in and out of the topic, it’s this: we can’t take for granted it’s going to be better for our children and grandchildren.

A 2C warmer world is a far cry from what we’ve lived in. A 3C or 4C warmer world is truly unimaginable. Too often we can believe politics is the only domain where this battle will be won: how you invest your disposable income, and what you choose to invest in makes a difference — depending on how much you earn, arguably far more than your vote.

Let’s all keep looking for the gap between the truck and the trailer.

Optimistically,

Owen C. Woolcock

3 Questions I Am Asking Myself This Week

1. The report’s authors estimate that the future of a liveable planet now relies, at least in part, on our removing anywhere from 100 billion to a trillion tons of carbon already in our atmosphere by end of century, depending on how much more we keep on putting into it. To put that in perspective, estimates show that we currently have the capability to take out about 5,000 tons a year through direct air capture.

2. The Prime Minister of Bangladesh is calling for developing countries to stop paying debts in order to fund essential adaptation now that the IPCC Report has definitively linked extreme weather loss & damage impacts to climate change. Not the last time an idea like this will be proposed.

3. Women almost everywhere in the U.S. are delaying having children, resulting in profound changes to American motherhood. The birthrate is falling fastest in places with the greatest job growth as women prioritise education and careers. What does this profound change mean for the carbon footprints of Mums, their children and the firms they work with?

If You Read Or Listen To One Thing This Week

A powerful chart: